Native Lawns

It may surprise you to learn that not all native grasses are tall feature plants. In fact in parts of Australia, pasture is composed almost entirely of native grass species. For the home gardener, that means you can have a native lawn that you can mow.

There are many local indigenous grasses that make lovely tough lawns. Some are available as plugs or you can sow it from seed and both are available at selected nurseries. You will get a better result using material sourced from local populations, as these plants will be better suited to the climate in your area.

How do native lawns benefit the environment?

Native grasses grow naturally under Australian climatic conditions. They have deep root systems, which means they require less watering than most conventional lawns and also enables them to survive periodic droughts and fires. They don’t need to be fertilised as often as most lawns, because they have adapted to Australia’s low fertility soil. Many native grasses have attractive flowers and seed heads, so interesting effects can be achieved by leaving carefully chosen areas of your lawn unmown. You can plant some indigenous wildflowers amongst the grass to create colourful areas of meadow. These are fantastic habitats for butterflies, pest-controlling insects and provide food for other wildlife such as birds.

Varieties suitable for lawns

There are several types of perennial native grasses suitable for lawns. The following species can be found growing naturally in most parts of Australia. You will get the best result using seeds or plugs that have been sourced from local populations. These plants will be better suited to the climate in your area.

Cool Season Grasses

These grasses do not go dormant over winter and, unless there is a prolonged period without rain, they remain green.

Weeping grass (Microlaena stipoides)

Native to most of the wetter zones of Australia and New Zealand, this cool climate species is as tolerant of dry conditions as the most drought-tolerant warm-season grasses.

Type: Spreads short distances by rhizomes underground

Height: Can be mown to any height required

Features: Weeping Grass is perhaps the most suitable native grass for creating the look of a traditional lawn. It can be mown regularly and will grow well in a wide range of soils, including acidic soils with a pH less than 6.

Tolerances: High drought tolerance; High frost tolerance; Medium salt tolerance; Shade tolerant. Low tolerance to heavy traffic and dog urine.

Wallaby grass (Austrodanthonia spp.)

Wallaby grass is widespread across the temperate areas of all Australian states.

Type: Tufted grass that should be mown no lower than 4cm.

Height: 30–80 cm

Features: Wallaby grass will survive without irrigation in soils from medium clays to light sandy loams with good drainage. It has white fluffy seed heads in spring and sometimes autumn.

Tolerances: High frost tolerance; High drought tolerance

|

|

| Left: Kangaroo grass (Themeda triandra) Right: Slender Wallaby grass (Austrodanthonia penicillata) Photographs: Ken Harris, Churchill, Victoria. Morwell National Park web site |

|

Warm season grasses

These grasses actively grow during warm weather. In winter, they have a period of dormancy that is usually casuses a change in leaf colour.

Kangaroo Grass (Themeda triandra syn. T.australis)

Kangaroo grass is one of the most widespread native grasses in Australia growing in every state and territory. It grows from interior arid regions, to the Alps and the coast.

Type: Tufting. Will tolerate mowing twice a year.

Height: 40-90cm

Features: As the foliage ages it changes colour from green to maroon. In summer the plant bears attractive rusty-red seed heads.

Tolerances: High drought and heat tolerance; Low to moderate frost tolerance.

Redgrass (Bothriochloa macra)

Redgrass occurs mainly in coastal, tablelands and slopes environments.

Type: Running, spreading slowly on underground stems

Height: 10cm

Features: Redgrass, as the name suggests, has green or reddish leaves. In summer and early autumn it produces reddish-purple flowering stems, which grow up to 80 cm. Its naturally low height means it may never need mowing!

Tolerances: High drought and heat tolerance; Low to moderate frost tolerance

How do I grow a native lawn?

Native lawns can be grown from seed and some are available as trays of plugs; both available in nurseries, or the seeds can be ordered online from www.nativeseeds.com.au.

While germinating, the seed should not be allowed to dry out and the lawn will require some additional watering to establish over the first few months. After the seed has germinated and put on some growth, help the grass to establish deep root systems by gradually watering for longer periods on fewer days. Eventually your lawn will survive with no additional water, simply rainfall. During droughts, the grasses may brown off, but if their root systems have been well established, they will resprout with the first good rain.

Native lawns require little, if any fertiliser. If you are mowing regularly, simply returning the clippings to the lawn may be enough. Native lawn species can thrive on low fertility soils, where weeds are at a disadvantage. If you avoid fertilising your lawn until you are sure that it needs it, you can reduce the number of weeds you get in your lawn too.

Sustainable Garden Design

Principles

Getting started

Your needs, wants and budget

Take your time

The design

Selecting plants

Special elements

Plant selection

Plant placement – plant stacking and hydro-zoning

Site details

Material selection

Know when NOT to DIY

Costs

Water features

Principles

1. To design a landscape that minimises the requirement for energy inputs. These inputs may take the form of petrol to run mowers, leaf blowers and line cutters; chemicals to treat pests; and fertilisers to promote growth, H2O, cleaning agents, stains and finishes to keep hard surfaces clean and well-maintained. Informed plant selection that reduces the need for maintenance inputs – e.g. gardens/landscapes that feature a high proportion of amenity lawn require much higher energy inputs than a mixed herbaceous/shrub planting. On-site treatment of green waste also reduces the need for energy input.

2. To design a landscape that minimizes the requirements for high water inputs, above that which naturally occurs in the particular region. This may be achieved via plant species choices, microclimate design (hydrozoning), mulches, water recycling etc.

3. To design a landscape that maximizes opportunities for biodiversity at all levels. This includes attracting wildlife, maintaining complex ecosystems, companion planting, considering the health of soil biota, recognizing the links between the elements of the garden and the organisms that inhabit it.

4. To design a landscape that maximizes vegetative biomass. This aids in carbon stabilization. For example a landscape that features a high proportion of paved or hard surfaces and/or high proportion of amenity lawn stores much less carbon than a landscape which features higher proportions of vegetative biomass. And we mean permanent vegetation, not material that must be constantly pruned or mown heavily, or seasonally replanted.Read more

Good Flies

Not all flies are bad! We are used to being concerned when we see a blowfly, thinking it carries disease, or being annoyed by those pesky common bush flies. But actually, they're all just doing their jobs. However, there are quite a few flies that are little more appealing than the common bush or blowfly and which are welcome visitors to sustainable gardens.

These are flies that are beneficial to us because they are predators of insects we often aren't keen on, or they are important pollinators.

Flies belong to the Order of insects known as Diptera. This order is characterised by some distinctive features, including the fact that members of the order look fairly similar.

- All flies have complete metamorphosis, that is, there is egg, larva (maggot), pupa and adult.

- The larvae have no true legs and are mostly referred to as maggots.

- Those huge compound eyes are common.

- And although some species are wingless, most have wings.

- The order also includes mosquitoes, gnats, midges and leafminers.

Robber Flies

(Family Asilidae)

Keep a look out for robber flies, for example. They aren't pretty but they are great predators. They are very successful predators with huge appetites, and they'll eat whatever insects happen to wander through.

Robber flies hunt by perching somewhere where they can see suitable prey and usually in a sunny open area. They catch prey in mid air, gripping with strong legs and modified mouth parts. Robber fly mouth parts have evolved to include a form of stabbing proboscis. The proboscis injects saliva containing toxic enzymes into the prey. Neurotoxins paralyse the prey and then proteolytic enzymes digest the protein in the body tissue. The fly then returns to its perch with the prey (as shown in the photograph above) and consumes the liquidised body tissue.

Robber flies can immobilise and eat bees, wasps, dragonflies, grasshoppers and even spiders.

Long legged fly

(Family Dolichopodidae)

This fly looks less like a fly because of its long dainty legs and thin body. It's metallic and quite bright with transparent wings that have interesting markings on them.

The adult Dolichopodid fly (as it is referred to scientifically) only grows to about 6mm in length. It preys on smaller soft bodied insects such as aphids, thrips and spider mites.

The larvae live in moist soil and under tree bark and are either scavengers or predators of other insect larvae.

Tachinid Fly

(Family Tachinidae)

There are 542 named Australian species of Tachinid flies, making the Family Tachinidae one of the largest families of the order. They all parasitise other insects, usually the larvae of moths and butterflies, but also the larvae or adult of beetles, and the adults of bugs and grasshoppers.

One species parasitises caterpillars just before they pupate. The result is that several flies emerge from the chrysalis instead of a butterfly.

The larvae of this fly are well adapted to their life inside their food!

Tachinid flies are extremely diverse in appearance. They can be quite drab or brightly coloured. And some even mimic wasps.

Hover Fly

(Family Syrphidae)

These unusual little flies have a characteristic flight pattern. They hover in one spot, then suddenly move forwards or sideways, then hover again. They can often be seen in large numbers.

Their black and yellow stripes mean they can be mistaken for bees or wasps, and that's their thing. They have actually evolved as wasp and bee mimics.

They all have large heads, large eyes and about 10 to 15mm in length. These wasp mimics tend to have a narrower waist.

The adults feed on nectar and pollen, and their larvae eat aphids, scale insects, thrips and can parasitise caterpillers. They are important pollinators of plants.

Some species lay their eggs in stagnant water, where the maggots become a predator of mosquito larvae. Another's larvae live by scavenging in ant nests. They mimic the ant's chemicals and move around undetected. A true cloak of invisibility!

Attracting Beneficial Flies

To attract these flies plant a wide variety of herbs and flowering plants which have a mass of tiny flowers aggregated on a stalk. Many are members of the family Umbelliferae (Apiaceae) like carrot, parsley, coriander, but there are many others such as alyssum, mints and related herbs like dogbane, lavender, tansy, yarrow, feverfew and lemon balm. Since mouth parts of these flies are small, the small flowers enable easy access to nectar. And at the same time, we can enjoy attractive masses of colour in the garden.

References

Kerruish, R.M. & P.W. Unger, 2003, 3rd edition, Plant Protection 1, published by RootRot Press, ACT

University of Sydney, School of Biological Sciences.

Photograph of Robber Fly courtesy of Keith Power, Toowoomba, Qld.

Photograph of Hover Fly courtesy of Troy Bartlett.

A Return to Nature – Organic Design

In a previous article on Wellbeing Gardening I summarised the research regarding the strong links between health and well-being and nature, but more so the benefits of gardening.

That article helps to explain why amazing landscape design shifts are taking place all over the world. To highlight how far even some architects may have come, here’s a little story. About 15 years ago I interviewed a prominent architect regarding his opinion of the designs of the finalists in a national competition. One of the designs was a stunning glass structure that was literally full of plants. I can no longer remember all the details but I will never forget the architect’s response to that one. He sneered:

‘The building would be okay if it wasn’t for all that cabbage.’

Fifteen years later, everything is getting covered in ‘cabbage’!

We are greening cities from roofs to walls. We have guerrilla gardening and school gardening. We have water sensitive urban design. Obviously we are also responding to climate change and resource conservation needs but I think it is strongly tied together. Along with this there has also been a move generally towards more organic design.

Natural Swimming Pools

It seems to me that natural swimming pools emerged as one of the biggest design trends of 2014, but they have actually been around in Europe for decades. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Garden_pond. In fact, Wayne Zwar from Natural Swimming Pools Australia says there are many public pools in Europe that are natural pools.

Natural swimming pools, by definition use no chemicals. Systems that use UV, ozone and copper/silver ion disinfection techniques are examples of non-natural methods and, by definition, are not natural swimming pools.

Natural swimming pools instead rely on biological processes to clean the water, called biofiltration. Aquatic plants oxygenate the water and, along with associated microorganisms, clean the water by continuously ‘gobbling up’ excess nutrients and impurities. The aquatic plants area (called the regeneration zone) is separated from the swimming area by a wall. The water looks natural, rather than the crystal clear of a chlorinated pool.

However, if the green tinge of a natural pool and the planted zone doesn’t appeal, there is another type of pool that provides the crystal clear look of the classic swimming pool but again relies on biological filters, except that the filters are tucked away out of sight.

Maintenance of natural swimming pools is less than that of chlorinated swimming pools but does require monitoring, a pump, and the usual skimming. The regeneration zone must be kept in good condition, after all, those plants and microorganisms are the cleaning system.

The second example given, where there is no regeneration zone but relies on running the water through a biological filtration system requires the least maintenance of all swimming pools.

Natural swimming pools must be constructed by a licenced builder and comply with Australian Standards.

Organic Landscapes

Organic landscape design is just as highly designed as any formal landscape, except that the landscapes look natural.

The organic redesign of former industrial sites has been happening for a long time, even the site of the Sydney 2000 Olympics at Homebush Bay was re-developed, as much as practicable at the time, with a very organic approach.

High Line Park in New York is one of my favourites. There were a lot of people involved in the redevelopment of these disused, elevated rail tracks, including the wonderful planting designer Piet Oudolf. Sections of the park are very organic in that remnants of the tracks have been left behind and allowed to develop a wild look, as though nature is reclaiming it.

Another large scale example is the London Garden Bridge, designed by Heatherwick Studio, but yet to be built. The Bridge will provide a pedestrian route between north and south London and features woodlands and meandering walkways.

The idea for the bridge was inspired by actress and campaigner, Joanna Lumley. A charity, Garden Bridge Trust, has been established to generate income for the building and ongoing maintenance of this wonderful initiative.

The Garden Bridge, like sections of High Line Park, really does look like nature is reclaiming the city, not a carefully designed structure and landscape, and that is the beauty of organic design.

Images

High Line Park: Beyond My Ken - Own work. Licensed under GFDL via Wikipedia - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:High_Line_20th_Street_looking_downtown.jpg#mediaviewer/File:High_Line_20th_Street_looking_downtown.jpg

London Garden Bridge: Heatherwick Studio, www.heatherwick.com

Frances Saunders is a horticulturist (B.App.Science), landscape designer and writer now based in Murray Bridge, South Australia after 25 years in Melbourne

Indigenous Plants

What is an indigenous plant?

Indigenous plants are not only native to Australia, but they are plants that occur naturally in your local area. Your local council will be able provide you with information on plants that are indigenous to your area.

Why plant indigenous plants?

Since white settlement our indigenous plants have been removed or out competed by exotic plants.

Indigenous plants were and continue to be an important food source for our local fauna. They are unique because they are perfectly suited to the environment that they belong to. This means that they should survive on local rainfall patterns and in the local soil.

Indigenous plants also:

- Provide habitat, shelter and food for our wildlife

- Help preserve the local plants

- Save water and money

- Enhance wildlife corridors and provide links between fragmented and otherwise isolated areas

- Contribute to the distinctive local character of an area

How to use indigenous plants

You can use indigenous plants in the same way you use exotics or other natives. They can be used in formal or informal gardens, mass planted for greater impact and a modern look or mixed in with existing plants to add different colours and textures.

There is an indigenous species for most garden situations, with choices of groundcovers, shrubs, climbers, trees, wildflowers and grasses. There are even shrubs to make hedges and borders.

Indigenous plants can also make great pot specimens. Small shrubs can be planted with ground cover species to tumble over the edges.

What local plants do I choose?

Indigenous plants can come from a range of growing conditions within a local area. Therefore it is wise to match the natural requirements of a plant to the planting site within your garden. For example, some species are naturally found in wet soil conditions, so these plants are ideally suited to an area of the garden that is naturally moist.

Attempting to match the plant’s natural growing conditions to those in your garden will ensure better plant performance. Knowing what sort of soil moisture and drainage the plant likes in the wild also helps in placing your plant in the correct location in your garden.

Cross-pollination with exotic plants or varieties from different areas can cause changes in the genetic make-up of the wild populations, known as gene-pool pollution. This has the potential to change the way the plants interact with other species in the ecosystem and may unfavourably alter the habitat requirements for the animals and insects that live in the area. In Victoria, this problem has occurred in plant genera such as Acacia, Coprosma, Correa, Grevillea, Nicotiana and Pittosporum.

It is important that the plants you choose have been grown from seed or propagating material collected in the local area, known as the provenance of a plant. A Common Correa (Correa reflexa) growing in one area can be genetically quite different from one growing 20 kilometres away. The regional differences between plants within a species can be as obvious as in these pictures.

Correa reflexa from Heathmont in Melbourne’s Eastern Suburbs |

Correa reflexa from Yanaki near Wilson’s Promontory |

Both pictures © Rodger Elliot

Caring for Indigenous Plants

The beauty of local indigenous plants is that they need little maintenance! They can be established in the same way as other plants, but from then on they require little in the way of water, fertilisers or pesticides. Here are some tips on helping them along.

- Soak the potted plant in water for 30 minutes before planting.

- Dig a hole at least twice as wide and slightly deeper than the pot.

- Gently tap out the plant and place carefully in the hole.

- Carefully fill the hole and firm down so that a saucer shaped depression results.

- Water the plant well.

If planting in the ground, loosen the soil to the same depth as the pot and twice as wide. This allows the root system to spread without much difficulty. Place the plant in the created hole making sure that the top of the soil from the pot sits level with the top of the soil in the ground. Back fill the hole and firm the soil down around the plant.

Indigenous plants have evolved on the local un-amended soils. Theoretically, no soil improvement should be necessary if the correct plants have been chosen. You could give your new plant an easier time of it however if you improved the soil. For example if there is heavy clay, the addition of a little gypsum will help to break it down. The addition of some well composted organic material - like a simple (no added nutrients) potting mix will break the soil up and increase the porosity.

Post Planting

Keep an eye on your plants in their first year. They may need a good soaking once a week during dry weather. Mulch around the plant to a depth of about 7.5cm, but ensure you leave a clear space around the stem to prevent bark disease. Top up your mulch every few years as it composts down.

Indigenous plants respond well to pruning as this mimics the grazing of native animals such as kangaroos. Pruning after flowering encourages new growth and further flowering.

Enjoy the beauty of our unique indigenous plants and the wildlife that is attracted to them!!

Fertilising

Fertilising is generally not needed for Australian natives but you can be guided by the origin of the plant. Plants from arid conditions will not need fertilising as they have evolved in nutrient poor environments. However plants from the more moist, mountainous parts of Australia with deep loamy soils, may benefit from a light feed in spring. If you do decide to fertilise, use a low-phosphorous fertiliser that has been specifically prepared for use on natives. High phosphorous fertilisers may harm some natives, particularly those in the Proteaceae family such as grevilleas, banksias hakeas etc

Pruning

They will appreciate a light trim after flowering to promote new growth, increased flowering and a fresh look. Regular pruning imitates the natural process of fauna eating the tips off trees and shrubs.

Staking

Staking is not necessary unless the plant is in real danger of toppling over. A plant should only be staked for 1 year, and it should be done lightly so the plant is still able to 'feel' some movement. This will help promote the root growth it needs to stabilise itself.

Caring for indigenous plants in pots

A little more care needs to be taken of plants in pots even if they are indigenous. In a pot, the plants have no way of sourcing their own water or nutrients. They are at your mercy. Therefore, in summer, they may need to be watered more often and twice a year in spring and summer they should be fertilised with a low phosphorous fertiliser. It should be remembered that potting mix is not what these plants have evolved in, so a very basic potting mix should be used. The plants may need to be repotted in the future too.

Replacing plants

As indigenous species can have a shorter life span, regeneration of garden plants is part of maintenance. Some old plants may be pruned back hard to help them regenerate. Replace plants as they finish or if allowed to become old and straggly. Simply break up the old plants and leave them on top of the garden bed as mulch where they will gradually break down. This will replenish the soil with organic matter and nutrients, thereby benefiting the soil's structure and health. There may also be a chance, given the right conditions that the plants self seed to produce the next generation.

Flora for fauna

Watching birds and animals play in the backyard adds a special dimension to the garden. Just by planting local species, you will attract the local fauna. You may also consider the following:

- Provide some water in the form of a pond or birdbath

- Plant thickly and prickly to provide nesting places and protection for birds

- Choose a variety of plants that will provide different food sources. For example, flowers for nectar feeding birds, and seed and fruit producing plants

- Leave logs and sticks on the ground to provide habitat for lizards and insects

If you are planting indigenous plants ask the staff at an SGA certified garden centre for some suggestions.

Information about indigenous plants from your area

Your local council will have information on plants that are indigenous to your area.

Environmental weeds

Some native plants have become weeds outside of their local area. Avoid using natives that are environmental weeds, for example Acacia longifolia (Sallow wattle), Acacia baileyana (Cootamundra wattle), Acacia decurrens (Early black wattle) and Pittosporum undulatum (Sweet pittosporum).

Fragrant Frangipani

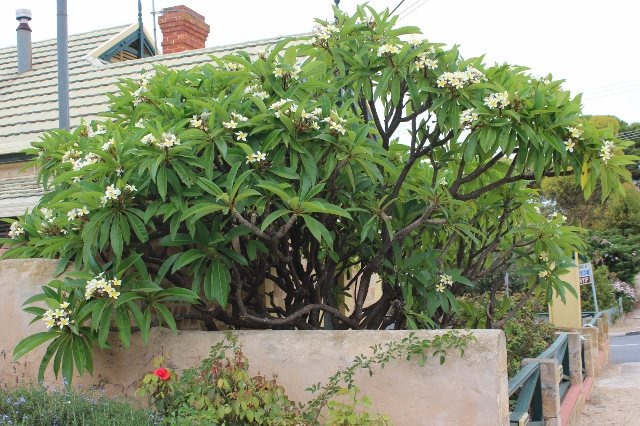

I was surprised to find a stunning Frangipani tree growing near where I live in the dry, hot climate of South Australia, so of course I took lots of photos and then thought, ‘I’ll be back in winter to take cuttings from you’!

My surprise was because I didn’t think Frangipani would grow (in the ground) so far away from its preferred climate of tropical and sub-tropical environs (it is a native of central America but not of Hawaii, as many people think because so many are grown there).

Frangipani is quite drought tolerant, in spite of its association with the tropics. In fact there is more of an issue with overwatering, as rotting can occur, especially of cuttings and young plants. However, it is frost tender, although the deciduous species would fare better but a late spring frost could be an issue for young and small plants.

The commonly grown Frangipani (Plumeria rubra), pictured here, is a small, winter-deciduous tree (although there are different species, so you need to check) that grows to about 5-6 metres in height and about the same in width. It’s related to Oleander and has the same milky, toxic sap, so that is a watch-point. However, the flowers have a divine scent and the tree has a lovely natural shape, so it’s quite irresistible.

The commonly grown Frangipani (Plumeria rubra), pictured here, is a small, winter-deciduous tree (although there are different species, so you need to check) that grows to about 5-6 metres in height and about the same in width. It’s related to Oleander and has the same milky, toxic sap, so that is a watch-point. However, the flowers have a divine scent and the tree has a lovely natural shape, so it’s quite irresistible.

If you live in northern Australia you will have access to a wider variety of cultivars with a variety of flower colours.

Frangipani can be susceptible to fungal diseases, such as downy and powdery mildew and frangipani rust, which can all be treated. Stem rot and black tip die back, as the names suggest, result in rotting stems and tip growth blackening and dying. Usually the result of stress, insect attack, or old age, the stems can merely be cut back to below the problem area. Copper based fungicides can be used to treat all of these problems.

Sap sucking insects do like the tree, but then if you encourage predators (such as lady birds) by not using insecticides, you will find this plant quite easy care. Planting flowers such as daisies, marigold, calendula, sweet alice and zinnias and herbs such as garlic chives, dill, feverfew and mustard will attract a variety of insects that provide a meal for the ladybirds. Those flowering plants also give shelter for predatory insects. Hemispherical scale is another nasty but again, encourage the predators. Be vigilant and a problem won’t get out of control. White oil can be used to control scale.

Propagation is by seed or cuttings. Cuttings can be taken at any time (watch that milky sap, it is a skin irritant too) but are best taken in winter as hard wood cuttings since the sap isn’t flowing and there are no leaves to worry about.

References:

http://www.allthingsfrangipani.com/frangipanis.html (This is an excellent website, with lots of detailed information on growing and information on history, introduction to Australia, myths and legends, and different species)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plumeria

Frances Saunders is a horticulturist (B.App.Science), landscape designer and writer now based in Murray Bridge, South Australia after 25 years in Melbourne

Photos: Frances Saunders

White Cedar - a Shade Tree

There is always something that makes a plant less than perfect but until I discovered the seeds of Melia azedarach were toxic to humans and other mammals and that it has become a serious environmental weed in some areas, this tree was perfect!

White Cedar (Melia azedarach) is a beautiful shade tree that is extremely drought tolerant. Oddly enough, though, the tree grows from the east coast (extending from the Victorian border right up to the top of Cape York) and the top of the Northern Territory, so its drought tolerance is a bit of a surprise.

Another surprise is that it is winter deciduous and we don’t have many winter deciduous plants native to Australia. In spring, just as the new glossy leaves emerge, the tree starts flowering and may continue to do so into summer. It’s worth planting this tree for the spring show alone. The starry lilac and white flowers appear in beautiful clusters. The flowers are also lightly fragrant, often described as chocolate-like.

Following on from the flowers are the seeds and for humans, one of the tree’s flaws as an ornamental. However, the seeds are hard, which has made them very desirable for use as beads, including rosary beads. As toxic as the seeds are and considering how widely the tree is planted, especially in parklands and as street trees, there have been only a few recorded poisonings, including dogs. The tree should not be planted where livestock can graze the seeds or leaves (leaves were implicated in 1974 as also containing the toxic compounds).

While toxic to animals, many birds are able to eat the seeds, which would have, along with human cultivation, helped the plant become the weed it has in some areas. It has become a serious problem in the Northern Territory (outside of its natural range) and Western Australia in particular but it has naturalised in all mainland states, so if you think you might be interested in planting it check that it’s not a problem where you are.

Now we can get back to its attributes. Along with considerable drought tolerance is its ability to tolerate temporary inundation. It also thrives in a wide variety of soil types (from sand through to heavy clay), is quite frost tolerant, and Grow What Where categorises it as being fire retardant.

While the flowers get most attention, the leaves are also a lovely feature of the tree. They are bipinnate – with many oval to elliptical leaflets, each from 20 to 70cm in length, that darken with age from the fresh, glossy green at emergence in spring. It really is a lovely tree to sit under, with all the leaflets dancing independently in a breeze.

While the flowers get most attention, the leaves are also a lovely feature of the tree. They are bipinnate – with many oval to elliptical leaflets, each from 20 to 70cm in length, that darken with age from the fresh, glossy green at emergence in spring. It really is a lovely tree to sit under, with all the leaflets dancing independently in a breeze.

The tree is defined as small to medium. But I wouldn’t pay too much attention to that. In its natural habitat it can grow to 35 metres in height, but is most often described as growing from between 6 to 12 metres in height with a canopy of 6 to 8 metres.

A little formative pruning as the tree grows will encourage it to develop its naturally rounded canopy, but other than that, it’s a pretty easy tree to maintain. It’s also responsive to pollarding. The hairy caterpillar of the White Cedar Moth, Leptocneria reducta, is its only serious nemesis, causing severe defoliation in large numbers.

Melia azedarach is a member of the Meliaceae Family, commonly called the mahogany family and while we most often refer to it as White Cedar it is also known as Persian Lilac, Umbrella Tree and Chinaberry, the latter being its common name, especially in the USA.

Propagation is by seed (no pre-treatment required) or cuttings.

A word of warning: because it produces seeds so readily, and they can be dispersed by birds, it can become a weed outside of its original habitat - especially in Western Australia and parts of the Northern Territory.

In the USA and New Zealand it is a declared weed.

References

Australian National Botanic Gardens: http://www.anbg.gov.au/gnp/interns-2008/melia-azedarach.html

Australian Native Plants Society: http://anpsa.org.au/m-aze.html

Peate, N., Macdonald, G. & Talbot, A., 2006, 3rd edition, Grow What Where, Bloomings Books, Melbourne

Conserving Water

Australia is the driest inhabited continent in the world, yet we use more water per capita than any other country. By reducing the amount of water we use in the garden, we can significantly save water and prevent the need to build more dams’. There are many ways gardeners can use water wisely to maintain a healthy garden.

On average we use just over one third of our household water on our gardens. By saving water in the garden, significantly more is available to allow healthy flow rates in our rivers and wetlands. This is essential for the wellbeing of the plants and animals that rely on our shared water resources for moisture and habitat.

Plan your garden

Think about the different regions you have in your garden. Some places may receive more sun or shade than others, some are wetter or drier and some are more exposed to wind. Choose plants that are suited to these areas.

Group Plants

Group plants together that have similar water requirements. For example, locate fruit trees and the vegetable garden close to each other. And don’t plant drought tolerant plants next to high water users.

Choose plant species carefully

Local indigenous plants are suited to the climate and soil of your area. Think about selecting some indigenous plants that will grow well in your area. Or grow plants that have low water requirements. Keep lawn area to a minimum, as it’s the biggest water guzzler in the garden! Plant trees to create shade and reduce evaporation. Wise plant choice can dramatically reduce the need for lots of watering.

Use the soil to store water

Good soil structure will hold water better than soil that has a low organic content. Soil structure can easily be improved through the addition of organic materials such as compost and manures – plus they provide food for your plants!

Use mulches to retain water within the root zone

Mulch is a fantastic water saver! It prevents evaporation by shielding the soil from the sun and reduces water runoff during rain and watering. Mulch also helps keep weeds down, protects plants from frost and heat, and improves soil quality.

Watering – not Wasting

It’s best to water in the cooler morning or evening and preferably when it’s not windy. Using a hose or irrigating without timers can waste huge amounts of water. Watering longer, but less often, will encourage deeper roots and increase drought tolerance of your plants. Think about installing an irrigation system that applies water at a known and appropriate rate. A rain sensor can be included to prevent the system watering the garden when it is raining! Fittings such as drippers and micro-sprays and perforated and porous soaker hoses are more water efficient than pop-ups and garden sprinklers.

- Water in the cool of the morning or evening

- Water longer and less frequently

- Mulch

- Compost

- Plant some indigenous plants and or shade trees

- Put in a watering system

- Reduce the amount of lawn

- Don’t cut your lawn too short

- Park the car on the lawn to rinse it

- Use a broom to clean up instead of the hose

- Check for leaks from hose fittings and replace.

- Have a look into Melbourne Water initiatives on http://www.melbournewater.com.au

- Also make sure that you keep an eye on the forecast, there’s no point in watering in the morning if you know its going to rain and cool down in the afternoon. http://www.bom.gov.au/ If you have a good watering routine that soaks deep to the roots every couple of days, your plants may be a bit wilty, but will be fine to wait a couple of hours.

Collect your own water

Rainwater tanks can store water to supply your garden throughout the year. Using greywater from the laundry and bathroom means a supply of recycled water is available every time you wash clothes and shower, even in the summer when rainwater is often scarce.

Water Restrictions

During periods of water restrictions some of these watering methods may not be allowed. Be sure to always check with your local water authority if you are unsure. Click here for a list of Australian Water Links.

Low Water Use Plant Information

Some general suggestions for drought-tolerant plants can be found on Tips Bulletin. For excellent, locally specific information on low water use plants see the following sites:

Silverbeet

Beta vulgaris L. Cicla

Time and space-poor gardeners might find vegetables that can be picked or cut continuously over time a better option than ‘once off’ crops. Silverbeet definitely measures up, and, it easy to grow and can be sown almost all year round in most regions. What more could you ask for!

Silverbeet is often called spinach but it’s not! They are both members of the same plant Family though…Amaranthaceae.

Silverbeet or Swiss chard, as it is also known, is actually a close relative of beetroot (in fact it’s a variety of the same species), but it’s grown for its leaves and stems.

Interestingly, in the United States and Australia the leaves are valued, while European cooks value the stalks. In fact they often discard the leaves or feed them to animals. The first varieties have been traced back to Sicily, rather than Switzerland!

Silverbeet seems to be more popular than spinach in Australia. Silverbeet is a cool climate plant that grows just as well in warmer climatic zones. In warm northern areas it can be sown almost all year, whereas in cold districts it is sown from early spring to early autumn.

Planting Schedule

Warm Areas: All year, except for the tropics where April - July are best

Temperate Areas: September - May

Cool to Cold Areas: September - March

Sowing Seed

It’s best to sow silverbeet seed direct where they are to grow. Rows should be about 500mm apart, and plants thinned to about 250mm between plants to allow mature growth. (Young silverbeet is an excellent salad vegetable as it has yet to develop the bitter taste of older plants).

Seed is best soaked for a few hours before sowing. Sow seed about 12mm deep.

Seeds take about 10 to 14 days to germinate, and thinning can commence when about 100mm tall.

Silverbeet prefers a slightly alkaline soil with at least a pH of 6 or above, and like all vegetables, needs well-drained, well composted soil that has the addition of animal manures.

Pests and Diseases

Apart from the usual problems associated with growing from seed (refer to the information sheet on Growing from Seed, silverbeet doesn’t really suffer pest and disease problems. Snails and slugs will of course enjoy young plants.

Harvesting

Silverbeet is the ultimate pick and eat plant, just take the leave you need and the plant will keep producing more leaves. Many leaves can be harvested at once without detriment to the plant because the roots store plenty of the carbohydrates necessary for additional leaf growth (and because older plants have larger roots, they can be quite denuded of leaves without a problem).

Varieties

The Seed Savers organisation lists about 12 different varieties of silverbeet. ‘Fordhook Giant’ is by far the most popular home garden variety for both its quality and high yield.

Diggers Seeds has developed Five Colour Mix, also known as Rainbow Chard, which is now very popular because of the variety of colours. (It also won an award!). The mix produces five different colour types, but in actual fact, the variation can be even more than just five. Rainbow Chard tends to be milder in flavour but just as productive as ‘Fordhook Giant’.

There are many other varieties available.

Information sources:

Yates Garden Guide, 42nd Edition, 2006, published by Harper Collins Publishers.

Blazey, C., The Australian Vegetable Garden, 2001, published by New Holland Publishers.

Fan Flower - Fabulous Native Ground Cover

Scaevola – groundcover species

What a popular garden plant this has become, and quite rightly so. The splendid fan flowers that give the genus its common name can be absolutely vivid, ranging in hue from white to blue and purple (rarely yellow). Read more

Ficus elastica (Rubber Plant)

Ficus elastica

Just what makes that little old ant, Think he’ll move that rubber tree plant

Anyone knows an ant, can’t - Move a rubber tree plant

But he’s got high hopes, he’s got high hopes, He’s got high apple pie, in the sky hopes

So any time you’re gettin’ low, ’stead of lettin’ go, Just remember that ant

Oops there goes another rubber tree plant

Whether its because of, or spite of Frank Sinatra’s 1959 hit song High Hopes, a humble rubber plant can be found tucked in the corner of homes around the globe. Attractive, easy to care for and an air purifier extraordinaire, you should have high hopes when you too add this fabulous little ficus to your living space.

Ficus elastica is a tropical plant from north-east India and south to Indonesia. It is ideally suited to growing indoors in large pots. In tropical parts of Australia, and even in warm and moist parts of the southern states, it can be grown in the ground. But be warned, it stops being a demure house plant once its roots get into soil. It can grow to 30 - 40 metres tall, sometimes more, with a particularly vigorous growth habitat. It also develops a wide canopy, drops large amounts of leaf litter and blocks light from smaller plants below. The roots of the ficus elastica tree can invade pipes and sewage systems and break up footpaths and driveways. Be warned, this tropical treasure is not for your average suburban backyard. It is a fantastic addition to your indoor space though.

Rubber plants are reported be effective at removing formaldehyde from the air of our homes and offices*. Formaldehyde is a volatile organic compound (VOC) and is commonly is found in resins and adhesives. It is also found in facial tissues, tobacco smoke, plywood and chip board and many other products.

The Rubber Plant’s ability to absorb toxins increases with exposure. This is because the microbes living with the plants break down the toxin, feed on it and also multiply.

Growing

Rubber plants have thick, dark green leaves which contain a latex-like sap. They can get by with less light than many other indoor plants for short periods of time, but for good strong growth and a healthy plant, your ficus will do better with good light. One way to determine the amount of light is to hold a piece of white paper upright where you intend to place the plant. Place your hand about 20cm in front of the paper in the direction of the window. If you cannot see a shadow there isn’t enough light for the plant to stay there for any length of time.

Rubber plants have thick, dark green leaves which contain a latex-like sap. They can get by with less light than many other indoor plants for short periods of time, but for good strong growth and a healthy plant, your ficus will do better with good light. One way to determine the amount of light is to hold a piece of white paper upright where you intend to place the plant. Place your hand about 20cm in front of the paper in the direction of the window. If you cannot see a shadow there isn’t enough light for the plant to stay there for any length of time.

Placing the plant near a window provides more light but at night time it may become too cold. Rubber plants do tolerate fairly low temperatures, hence their ability to grow outside with gusto in even southern Australia. Give your tree a vacation outdoors for a week or two in the warmer months but make sure it is a shady spot. Indoors, avoid placing the plant pot near heaters or central heating vents. This can reduce the humidity around the plant and leave it susceptible to pest attack.

The stem of Ficus elastica is sufficiently strong that they do not require staking. Plants can grow up to 2.5 metres when grown indoors.

When potting up, choose a free draining potting mix and pot. Plants left sitting in water logged soil can drop leaves. Water lightly and allow the soil to dry between watering. Test the soil with your finger before watering. If the soil is damp and sticks to your finger your plant does not need a water. Many indoor plants are killed with kindness by well meaning owners who overwater them!

Though this plant does not have a high nutrient need it will benefit from a light monthly feed of weak liquid fertilizer or heavily diluted worm wee in the growing season.

Ficus elastica can become root bound quickly so the plant will need to be re-potted as it grows. Take the plant out of its pot (over some paper to catch any potting mix that is dislodged). If you can see roots the plant has outgrown the pot.

If the roots are wound around within the old pot, loosen them so that they don’t continue to grow in a circle. If the roots are tightly matted, cut them (slice down the side of the root ball in several places with a pair of secateurs), so the roots are able to grow out into the new potting mix.

Pest and disease problems

These plants are pretty tough and don’t suffer from too many issues. Generally if the plant looks unwell, is dropping leaves or yellowing off it’s a sign that it’s either in the wrong spot, root bound or getting too much or too little water.

Rubber Tree plants can succumb to attack by scale insects, spider mites, thrips or mealybug if their growing conditions are not ideal.

Note: Rubber plant material can be toxic to small animals (including cats and small dogs) as well as young children. The sap can irritate the skin and plant material can cause nausea and vomiting if ingested. Care should be taken in homes where little people and little critters have access to house plants. Those with severe latex allergies and sensitive skin should avoid growing this plant.

Refer also to our Fact Sheet on Indoor Plants:

Information sources

Information sources

* Wolverton, B. C., 1996, Eco-Friendly House Plants, Viking Penguin.

Weidenfeld, G. & Nicolson, 1999, 500 Popular Indoor Plants for Australian Gardeners, Random House Australia

Noxious Weed - Hawthorn

Crataegus monogyna

This noxious weed is prohibited entry into Western Australia and is regionally controlled in Victoria and South Australia where it is capable of spreading beyond the areas it currently occupies.

They can be found in natural areas as varied as grasslands, woodlands and forests, as well as along roadsides and in paddocks. Their invasive success is due in part to their tolerance of a wide range of soils and conditions. They are also successfully spread is via birds who digest the seed, enhancing germination and spreading it over a large area. It also suckers and can be spread by other animals and by dumping garden waste in natural areas.

Its environmental effects are not just limited to natural areas either. In the garden it harbours pests such as light brown apple moth and pear and cherry slug. They usually have long thorns which makes removing them from bushland even more arduous.

So if they are growing on your property you would be doing a service to the Australian environment by pulling them out and disposing of them carefully.

Banner image: Meneerke bloem [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons

Growing From Hardwood Cuttings

A cutting is a piece of stem, a leaf, or root that develops roots when placed in suitable medium and in the right conditions.

It's very satisfying as a gardener to gently knock the potting media from a cutting after waiting and caring for it for weeks or months, and seeing a nice group of fat white roots.

Not that all cuttings need that much care or that much waiting - it just depends on the species of plant.

Hardwood cuttings are about the most carefree of all. Hardwood cuttings are pieces of stem from deciduous shrubs or trees taken during winter when the plant is dormant. The stems are very firm.

Softwood cuttings are those taken from young growing stems and, because these are prone to wilting and drying out rapidly, they need a lot of care, often with misting systems.

Semi-hardwood cuttings are taken later in the growing season, when the new growth has firmed up a bit.

Taking Cuttings

Hardwood cuttings are pieces of stem that are up to 20cm long and between 5 and 20mm in diameter. There should be four to six nodes on each piece - as can be seen here.

The only point to watch is that you don't pop them in the media upside down! For pieces of stem where the direction of the buds is not visible this can be an easy mistake. When taking the cutting, make a slanting cut at the bottom just below the last node and a straight cut about 6 to 12mm above the top node.

Hormone treatments that promote root development are available from garden centres, either in powder or liquid form. Hardwood cuttings often don't need root promoting hormone treatments. In fact some hardwood cuttings will sprout roots when simply pushed into the ground. Weedy plants such as willows and poplars can do this.

Always ensure the cuttings are potted up as soon as they are taken. Dip the bottom in rooting hormone, if necessary, make a hole with a pencil or dibble - about 5cm deep, and carefully place the cutting in the hole - about one-third of their length - and firm the mix around it.

And hardwood cuttings often don't need special conditions, just a protected spot in the garden, where there is light but not direct sunlight. However, cuttings will strike better with some warmth. A simple frame covered in clear plastic or even a plastic bag over a pot will provide more heat and humidity.

Propagating media or seed raising mix is suitable for hardwood cuttings. These can be bought from garden centres, but you can also make your own. Mix two parts of coarse sand and one part of premixed coco peat or vermiculite, or, if you need a mix that holds more water, try one part coarse sand and one part premixed coco peat or vermiculite. Adding crushed charcoal will keep the mixture clean and more open.

Plants will need to be gradually hardened to full sunlight once roots have developed.

Swapping Seeds

It seems to be quite a common practice to swap seeds with overseas friends and relatives. This seemingly benign and happy pastime has a dark side though. Australia is free of a number of nasty pests and diseases that plague other countries. One seed harbouring a disease or pest could open a Pandora's Box of catastrophic problems in this country.

For example, many plants in the Myrtaceae Family, which includes Eucalyptus, Callistemon, and Lilypilly, are susceptible to a variety of rust diseases. The most serious is Guava Rust, caused by a fungus, Puccinia psidii. The Australian Quarantine and Inspection Service (AQIS) lists plants known to host this fungus. The seeds and plant material from these plants are subject to strict import conditions.

And there's always the chance of accidentally introducing weed seed too.

Unfortunately for the home gardener AQIS's importation requirements are so stringent and costly that the exercise isn't worth it for a few seeds. But please, for the sake of Australian horticulture and our natural vegetation, do not be tempted to flout the rules.

Interstate

There are many legitimate Australian-based mail order companies selling seeds and plant material, such as Green Harvest (www.greenharvest.com.au) and Diggers Seeds (www.diggers.com.au) but you will note that even these companies are often not allowed to send plant material to Western Australia and Tasmania because of the quarantine restrictions in those states. This is because Western Australia and Tasmania have even less pest and disease problems than other states of Australia and, quite sensibly, these states want to prevent any future problems.

Shown here is a collection of Blackwood seed (Acacia melanoxylon) collected for revegetation projects (photograph courtesy of Greening Australia).

What can we do?

Discourage friends and relatives from sending seed and any other plant material from overseas, unless the material goes through the proper procedures (such as applying for permission and then quarantine).

Even interstate movement of seeds and plant material should be discouraged (and remember it is illegal in many situations), unless the material goes through the proper procedures.

Always check with AQIS authorities in your state before sending or receiving plant material.

Seed Savers Network

There's a better way to exchange seed with like-minded people and organizations - through the Seed Savers Network. The photograph here shows Michel and Jude Fanton of the Seed Savers Network, who offer advice to community gardens on setting up local seed networks. (Photograph courtesy of Australian City Farms & Community Gardens Network).

Community Gardens

Community Gardens can be found dotted around cities everywhere. Land is often supplied by local councils. It is then divided into small garden allotments, which people apply to use.

Community Gardens are essentially produce gardens and, as can be seen here at the Flemington Community Garden, often fulfill a very necessary service for people living in high-rise apartments.

This garden at Flemington has about 130 allotments, a chook shed, and rustic shelter and seating. The design includes raised beds for less-mobile gardeners.

SGA member nursery, Garden of Eden, also runs a community garden project from its site in Albert Park (shown here with the historic former railway buildings backdrop) (Photograph courtesy of Cultivating Community).

More information can be found at: www.communitygarden.org.au

Community Gardens Network

The Australian City Farms and Community Gardens Network is an informal, community-based organisation linking people interested in community gardening across Australia. More information can be found at: www.communitygarden.org.au, where there are links to state-based organisations, such as Cultivating Community in Victoria.

The aims of the network include:

- facilitating the formation and management of community gardens and similar social enterprise by making available information and, where possible, advice

- promoting the benefits of community gardening and urban agriculture.

Within the limits of its capacity, the network will:

- advocate on behalf of community gardeners

- provide information on the website that is adequate and accurate

- provide presentations and advice to local government, other institutions and communities interested in establishing community gardens

- document the development of community gardening in Australia

- provide a list of contacts through which the public may contact community gardens.

How to make a Community Garden

Here are some tips for getting a community garden up and running.

Bottom Up Approach

Working from the bottom-up is the most common:

- a group of people get together and work out what they want

- the group approaches the local council or some other institution for help in finding land and, perhaps, for other assistance

- when the group has gained access to land, they design the garden and start to cultivate it.

This approach builds ‘ownership’ of the community garden because the people who work the garden put in all the effort.

Top Down Approach

The top-down approach is favoured by professionals such as community workers and local government staff:

- the professional workers become interested in the potential of community gardens to build a sense of community or to improve the nutrition of the people they work with

- with their existing contacts with government, schools or churches they obtain land and funding more easily than citizens using the bottom-up approach

- they then have to popularise the idea of the community garden among the target group they believe will use the garden

if successful - and it might take some time – they then make use of a council landscape architect to design the garden; alternatively – and this might be the better solution because it builds ownership of the garden - they might find someone in the community who can lead a design workshop with the would-be gardeners, turning what could have been a professional-led solution into a participatory process.

The good news is that the top-down approach can succeed if the community or local government worker has the patience and persistence to build support for the garden within the community.

Once the idea has been discussed with the local community, it is a good idea is to organise a mini-bus tour of three or four existing gardens. Some councils may help with this.

Be sure to visit a variety of gardens, as to expose community members to a range of approaches to community gardening.

MORE INFORMATION

Community Gardens: A Celebration of the People, Recipes and Plants, by P. Vardy and P. Woodward, (published by Hyland House).