Sustainable Garden Furniture

Even if we live in an apartment, most of us have some sort of garden furniture – even if it is just one chair. Traditionally made out of wood, tables and chairs are now available in a variety of materials which differ considerably in their sustainability. Even wood is not always the most sustainable option. In considering whether garden furniture is sustainable, it is wise to consider the materials, energy inputs associated with manufacture and transportation, durability as well as social aspects of production. Most products do not undergo a whole-of-life sustainability assessment, but there is information available to help us make wiser choices.

Timber

Jarrah, teak, merbau and western red cedar are timbers used for outdoor furniture in Australia. Western red cedar furniture is not so common here as it grows in Canada and North America and its export is restricted. However, since trees are fast growing and reach heights of 70m, it is widely claimed to be a sustainable timber when grown in plantations.

Teak is a rainforest timber, sourced from Asia. While rainforests are host to 80% of the species that have been recorded, around 324 square kilometres are destroyed yearly with a similar amount degraded daily. This not only reduces habitat for dependent fauna, it also decreases the amount of vegetation which acts as a sink for carbon dioxide.

Jarrah is popular because of its resistance to rot and attractive red colour when new. It grows in the south west of Western Australia. It is an important habitat tree because of its height (up to 40 m) and trunk diameter (3m).

Merbau, also known as kwila or ipil, comes from a slow growing rainforest tree taking 75 – 80 years to mature. Because of the attractiveness of its wood, extensive and illegal harvesting has caused Merbau trees to be classified as endangered, likely to become extinct in 30 – 35 years.

Recycled timber

You might also look out for tables and chairs made either wholly or partly out of recycled timber. There seems to be an increase in manufacturers of such products.

Plastic

Due to increasing industrialization, plastic has become a cheap alternative to timber. But most of it is unsustainable because of the high material and energy inputs in its manufacture which also produces polluting waste products and its lack of durability due to degradation by sun and rain in an outdoor environment.

Due to increasing industrialization, plastic has become a cheap alternative to timber. But most of it is unsustainable because of the high material and energy inputs in its manufacture which also produces polluting waste products and its lack of durability due to degradation by sun and rain in an outdoor environment.

Recycled plastic

Over recent years, high density polyethylene (HDPE) derived from recycling plastic has offered a useful alternative for strong furniture structure. It withstands outdoor conditions, will not rot, crack or be attacked by pests, does not need sealing or maintenance, is non-toxic and can be screwed and sawn in the same way as timber. Available in a range of natural colours - although it can be painted - it has a long life. It is unlikely to be blown away since it is heavier than normal plastic furniture.

However, be sure to check the details of the nature of any such product – we have observed furniture that is made from plastic that has similar properties, but is not made from recycled material.

Stainless Steel

Much outdoor furniture is now made from stainless steel in combination with other materials. However, steel requires high energy inputs to manufacture. But it is durable - resisting corrosion - can be recycled and more than 50% is made from stainless steel scrap which has been re-melted. It is light, but strong, and is easy to maintain.

If it has a high recycled content and is in combination with glass or a sustainable or recycled timber (as a table top) it is a relatively sustainable product. However, stainless steel chairs often include plastic strapping (possibly made from dyed acrylic) for sides or seats. Table tops and seats may be made from unsustainable timber e.g. kwila or rosewood. Also take care with the use of “eco” in brand or store names – it is sometimes used inappropriately.

Aluminium

Aluminium

Furniture made from this metal has similar advantages and disadvantages to stainless steel. It is somewhat lighter which may be a benefit for moving furniture around, but remember that a large amount of energy is used in extracting aluminium from bauxite and subsequent smelting.

Wicker

This is the term used to describe the result of weaving various types of material to create furniture. Traditionally it was made from different species of grass ranging from bamboo, cane or rattan to sea grass. Sometimes a combination is used with bamboo constituting the supporting frame and woven, finer material comprising seats and backs of chairs. The resulting furniture is stylish and natural-looking.

The species of grass used generally grow rapidly, so harvesting is usually sustainable. However, although this furniture withstands exposure to weather it is not as long lasting as stainless steel and, therefore, is usually used under some sort of cover.

The species of grass used generally grow rapidly, so harvesting is usually sustainable. However, although this furniture withstands exposure to weather it is not as long lasting as stainless steel and, therefore, is usually used under some sort of cover.

Some wicker furniture uses woven vinyl or plastic which involve high energy manufacturing inputs and also creates chemical wastes that need care in disposal. So just because it is called “wicker” does not make it sustainable.

Soft materials for seats or cushions

Many types of outdoor furniture use flexible material for slung seats or backs of chairs or to cover cushions. Much of this material is plastic of some sort:

Vinyl (PVC), polyester fabric coated with PVC or dyed acrylic which sometimes incorporates cotton. Vinyl gets very hot to sit on and cannot be recycled. The others vary in durability.

The most sustainable fabric is probably canvas made from cotton or linen (it used to be hemp). It is a natural material, very durable and cheap. However, remember that cotton, unless organic, has been grown with an amazing number of pesticides which pollute are and waterways. However, production of fabric and dying it usually removes residual pesticide.

Longevity vs Manufacturing Inputs vs Cost

It can be tricky to weigh up durability, the environmental impacts of component materials and the cost. In general, long-lasting, low environmental impact materials tend to require a higher initial outlay. However, if they are durable, requiring little maintenance, then that cost is worthwhile. Their capacity to be recycled at the end of their lifetime is also worth taking into account.

Greening Cities

Although beautiful old gardens are disappearing, there are initiatives to green cities. As old houses are pulled down to make way for new large ones, dual occupancies or apartment blocks built with very little garden and few trees, we sigh and wonder what the world is coming to. But Vision 202020, started in 2013, (now Green Spaces Better Places) was an attempt to increase green space in Australia’s cities so they can cope with a warming climate and pressures of modern living.

So far, there are 466 organisations in its network. Many government bodies, including local government, have signed up to it, are aligning their planning with it and are establishing specific projects to achieve this vision. Nationwide signatories include cities of Adelaide, Campbelltown, Ballarat, Central Goldfields, Canterbury, Melville, Fremantle, Gold Coast, Geelong, Stirling, Subiaco, Sydney, Vincent, Launceston, North Sydney, Penrith, Mundaring, Banyule, Darebin, Kingston, Melbourne, Yarra, Moreland and Whitehorse. Many other organisations, including 23 developer, construction companies have signed up along with many landscapers.

Why green cities?

There are many reasons to increase green space. See our previous article by Dr. Gregory Moore for more detail. Trees and other greenery moderate temperature and associated human comfort through shading, protecting from wind and through evapotranspiration. They also reduce glare and noise.1 These functions of vegetation lead to human health benefits such as reducing the cancer risk of sun exposure, reducing heat-related illness, improving mental wellbeing and reconnecting children with nature to improve their creativity and physical activity.

These benefits, in turn, flow on to economic benefits such as increased property values due to the aesthetics of trees and gardens, reducing costs of infrastructure and mechanical heating and cooling through shading and reducing health costs. A well-vegetated suburb has decreased costs of maintaining storm water systems because vegetation slows water flow and reduces soil erosion.

At least equally important are benefits to nature and ecosystems by absorbing carbon dioxide and providing wildlife habitat.

The big challenge

Urban green space has been decreasing since the 1980s. Then, houses typically took up 20 – 30% of house lots but by 2010 they took up at least 35-40%. So backyards shrunk from 150 square metres to an average of 100 square metres. This reduction in green space was not due to urban consolidation, but to growth of house sizes – in the 1980s it was an average of 161 square metres, but by 2012-13 it was 241 square metres – a 50% increase! This means that green space in suburbs is increasingly in the form of very narrow strips between and behind houses – spaces that are not particularly useful for growing canopy trees, providing wildlife corridors or for outdoor relaxation or children’s play.

Urban green space has been decreasing since the 1980s. Then, houses typically took up 20 – 30% of house lots but by 2010 they took up at least 35-40%. So backyards shrunk from 150 square metres to an average of 100 square metres. This reduction in green space was not due to urban consolidation, but to growth of house sizes – in the 1980s it was an average of 161 square metres, but by 2012-13 it was 241 square metres – a 50% increase! This means that green space in suburbs is increasingly in the form of very narrow strips between and behind houses – spaces that are not particularly useful for growing canopy trees, providing wildlife corridors or for outdoor relaxation or children’s play.

Progress so far

Most of the projects associated with Greener Spaces Better Places have involved research, data gathering, policy and planning. These include:

- A database which shows which plants grow best under what conditions

- Developing a simple soil testing kit

- Developing a straightforward process to bring together councils, residents and businesses to create a collaborative low cost composting program

- Projects associated with funding and investment such as how best to share risks and costs of creating more green space

- A directory of good design which showcases examples of creating or improving green space

- An approach to creating common green space when individual dwellings have little or none around them

- Expanding Permablitz so that more people and organisations can access methods of permaculture

- A process for creating a community action plan to involve more people

Is this just all talk and paper work?

It might look that way, but meeting the somewhat ambitious goal of 20% more green space in just 7 years requires development of innovative and clear approaches to getting the work done.

One of the most interesting projects is a workbook How to grow an urban forest. This was the result of collaboration of different levels of government. Aimed primarily at local councils, the workbook sets out 10 very clear steps. A key component is engaging the broader community, explaining why it is so important that there is more green space and enlisting their aid rather than just changing planning laws and planting trees on council-owned property. This book contains examples of cities that have started the process of greening.

What can gardeners do?

As gardeners seeking a more sustainable world, we are probably saddened as we see gardens engulfed by multiple occupancies and houses of monumental size. Do we really need such large houses? Can we convince State and Local governments to change planning laws that permit this gobbling up of green space by over-sized buildings?

As individuals, there are many things we can do:

- Create green walls and roofs. Research is advancing on the best plants, soil and growing conditions. An excellent example of such research is being conducted at the University of Melbourne, Burnley Campus (shown at right). Many businesses are providing systems to enable these for homeowners.

- Grow canopy trees

- Plant tall shrubs and creepers along fence lines and walls

- Replace hard surfaces with vegetation – grass and lawn alternatives work well for walkways and driveways. There are now systems for providing a rigid underlay for grassed driveways.

- Encourage family, friends and organisations to which you belong to green-up

- And, if you are politically-minded, you can approach your local council and support their initiatives to green your local area.

References

- Hall T. 2010. The life and death of the Australian backyard. CSIRO Publishing.

Are You Setting the Trend?

Are you following the current gardening trends or are you an individualist? Trends develop because of changes in the rest of the world, such as COVID-19, or gradually evolve as friends, family and neighbours do something which provokes interest from others. Of course, the media plays a very important role in establishing trends too. Trends in 2019 - 2020 are rather different from those in 2018 - 2019.

Growing your own food

While productive gardening was high on the list last year, it wasn’t at the top. But now, almost certainly because of worries about running out of food and people having more time during the coronavirus lockdowns, growing your own food has become the leading trend. It goes under many names – productive gardens, Victory gardens and foodscaping.

Return of Victory Gardens

Due to the loss of supply of vegetable and flower seeds from Germany during World War I, ornamental gardens in Britain, America and elsewhere were converted to growing vegetables. This occurred in both public and private gardens to support the supply of food for both those fighting the war and those at home. The importance of such gardens arose again during World War II and the term “Victory Gardens” was given to them and popularised in the USA and the UK. As well as in back gardens, they were located in parks, railway reserves, backyards and even bomb craters. Eleanor Roosevelt, the wife of the USA’s President at the time, planted a Victory Garden on the lawn of the White House. The idea was revived a little more recently by Michelle Obama.

They were promoted not only to boost the food supply but also to improve mental wellbeing of citizens by providing them with a sense of participation in the war effort, opportunities to cooperate with others and share food with neighbours.

In Australia, in 1942, the then Prime Minister started a campaign “dig for victory”.

After world War II was over, these gardens were no longer essential as commercial food supplies were restored, so the focus on productive gardening diminished. Currently, the crisis created by COVID-19 seems to have reactivated backyard "Victory" gardening and people have started to worry about food supply even though Australia’s commercial food growing has not been affected. Garden centres and seed suppliers have been swamped by demand so that many were out of stock quite quickly. SGA has observed a dramatic increase in the numbers of people viewing our website for more information about how to establish and maintain a productive garden.

Accompanying this trend, perhaps because of concerns about income security during lockdown, there is more interest in minimising waste, recycling, composting, repurposing various items in garden construction and “double purpose plants” e.g. plants that are attractive but do something useful such as marigolds to attract predatory insects to attack pests.

Relaxation and Peace

In both Australia and overseas there is an increasing emphasis on landscaping which aids relaxation and a feeling of calm. So there is more interest in a focus on creating an urban oasis using swimming pools and fountains with the sound of trickling water to create a place of beauty. This trend has been reported in Australia, North America and Europe.

In both Australia and overseas there is an increasing emphasis on landscaping which aids relaxation and a feeling of calm. So there is more interest in a focus on creating an urban oasis using swimming pools and fountains with the sound of trickling water to create a place of beauty. This trend has been reported in Australia, North America and Europe.

Low Maintenance

Associated with busy lifestyles (before the coronavirus has kept us at home and reduced incomes) and with efforts to create a relaxing atmosphere are attempts to minimise upkeep by planting perennials and planting densely to reduce weed growth.

Using more surfaces for plants

Here we see a variety of feature walls perhaps with a few cascading plants or with a series of pots containing flowers, herbs, fruits e.g. Strawberries or vegetables. There is also more interest in rooftop gardens.

Here we see a variety of feature walls perhaps with a few cascading plants or with a series of pots containing flowers, herbs, fruits e.g. Strawberries or vegetables. There is also more interest in rooftop gardens.

Other trends

Varying more in predominance in different countries, a number of other trends can be observed:

- More sophisticated plant palettes with more species variety - aesthetically pleasing and adding to biodiversity

- Custom build garden furniture

- More professionally designed gardens

- Indoor plants - as we become more aware of the health benefits they provide in cleaning the air and, if we live in apartments, some contact with nature.

- specialised lighting to allow us to enjoy the garden at night.

So are you a trend-setter or a trend follower?

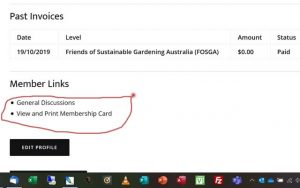

You can tell us and others in the FOSGA General Discussions – just go to Your Account, scroll down and click on General Discussions to respond to the topic.

You can tell us and others in the FOSGA General Discussions – just go to Your Account, scroll down and click on General Discussions to respond to the topic.

Local Food and Harvest Swaps

Groups which swap and share food and other local produce have been increasing in number for more than a decade. As the Food Swap Network in North America states "A food swap is a recurring event where members of a community share homemade, homegrown, or foraged foods with each other."

Motivations are many and varied:

- enabling excess garden produce and plants to be used rather than wasted

- sourcing food that is largely grown without chemicals

- minimising food miles through growing and swapping locally

- increasing access to a diversity of food

- accessing seeds and seedlings

- gaining knowledge from other gardeners

- sampling unfamiliar produce

- networking and making friendships with like-minded people

- in some cases, to listen to talks by guest speakers

Many food swaps have a webpage or a Facebook page, but since there are so many we are not going to list them all. Rather, below we show websites that have compiled such lists, some with searchable maps. Some of the sites, however, especially those with a national coverage, include other sources of local food such as farmers' markets, pick-your-own farms and a variety of other locations - even restaurants. Criteria for inclusion in these sites vary, with only some emphasising ethical or sustainable production.

Victoria seems, so far, to be the 'food swap capital' of Australia, followed by NSW and South Australia. But we have observed that not all swaps appear in these listings. So please check if your swap is listed on the sites below. If it is not, and you would like it to be included, please contact either Local Harvest or the umbrella organisation listed below that is most relevant for you.

On the other hand, if you are not a member of a swap, see if there is a one near you! Or start one! Local Food Connect and Cultivating Community have guides for starting a swap.

On the other hand, if you are not a member of a swap, see if there is a one near you! Or start one! Local Food Connect and Cultivating Community have guides for starting a swap.

National

Local Harvest

Local Harvest was based on a similar organisation in the USA and was initiated by the Ethical Consumer Group to enable you to have a closer connection with food and to find local and more sustainable food sources. It partners with Sustainable Table and the Sustainable Living Foundation.

It has a national directory and maps all types of ethical food sources apart from supermarkets or the industrial food system i.e. food swaps and shares, community gardens, restaurants and cafes, farmers’ markets, ‘pick your own’ farms, products sold at farm gates, organic retailers, bulk buying opportunities. It also provides information on producing and storing your own produce and sustainable living. To find resources near you, just search their website using your postcode.

Ripe Near Me

Based in Adelaide but with a searchable map and national reach, this website links individual buyers, rather than food swaps, with producers of food that is in excess to be sold, traded or sometimes given away free of charge. Some foraging sites are also listed.

Area-based

Victoria

Local Food Connect - around 30 swaps in the North East of Melbourne.

Moreland Food Gardens Network - swaps in a number of Melbourne suburbs (not just in Moreland).

My Smart Garden - a network of home and community gardens. Some community gardens hold regular food swaps.

Macedon Ranges Sustainability Group - this includes the Woodend Home Produce Exchange.

South Australia

The Urban Orchard is a network of food swaps in the inner suburbs of Adelaide.

NSW

Food Fairness Illawarra lists community gardens (some with food swaps) in the Illawarra area, around Wollongong, Shellharbour and Kiama.

Queensland

Brisbane Kids and Families Magazine list a number of swaps including those run by community gardens.

Western Australia

Slow Food Perth lists a number of farmers' markets.

Insects and Extinctions

What is happening to insects? Do you see the same number of insects in your garden as you did a few years ago? Research in the northern hemisphere shows that there are significant declines in insect numbers. A review of scientific data in 2019 shows that rapid rates of decline in insect numbers threatens 40% of insect species with extinction over the next decades possibly leading to “insectageddon ".

In Australia, there is not enough scientific data yet to say if the same conclusions apply here. However, it is known that some insect populations are declining e.g. the green carpenter bee.

Should We be Concerned?

To many people, insects are just a nuisance, but they actually play a pivotal role in nature. They are important in maintaining ecological balance. They provide food for many birds, reptiles, other small animals and fish. They clean up/recycle waste and decaying plant and animal material and some also feed on or parasitise larvae of pest insects. One of their most important roles in the world’s ecology is that of pollinators of plants. This function is vital for production of food crops and is a reason that we are so concerned to prevent reduction in bee populations.

Since insects comprise the largest animal group on the earth and represent about two thirds of land-based species, we need to be very concerned about major changes in their populations.

Causes of Decreasing Insect Populations

Many aspects of our modern world are responsible for loss of insects:

- Pesticide use – in agriculture, gardens and inside dwellings. Many such as the commonly used group of chemicals, neonicatinoids

are not specific for pests and kill many other insect species as well.

are not specific for pests and kill many other insect species as well. - Agriculture’s dependence on large scale monocultures. These support only a small number of insect species displacing other species which do not thrive or reproduce in the absence of a natural diversity of plants species.

- Loss of habitat due to agricultural monocultures and urbanization. Both have led to removal of wetlands and naturally diverse vegetation which provide food, shelter and breeding grounds for insects.

What You can do to Help Insects

Each of us can do something to help prevent insect decline continuing:

- Reduce or stop use of insecticides. There are many alternatives that protect plants from insect attack. In other articles on SGA’s website there are suggestions for particular pests. Some examples are hosing them off or covering target plants with fine netting.

- Reduce (or get rid of) your lawn area which provides little food or shelter for insects

- Plant your garden with a wide variety of insect-attracting plants to provide them with food and shelter e.g. Marigolds, perennials with composite flowers like Sweet Alice and Yarrow, herbs with perfumed flowers or leaves, sunflowers.

- Create some “messy” spaces in the garden to provide shelter and breeding locations – pieces of timber, old bricks, stones, dense shrubs and ground covers. In particular, plant ground covers and mid-storey plants that are indigenous to your area - they are best at attracting indigenous insects.1

- Make or buy an insect hotel which will give insects a home and look attractive too.

- When you buy food, choose that which hasn’t been grown using pesticides. These would be labelled “organic”, pesticide-free”, “chemical-free” or “biodynamic”. Boosting sales of such food leads to growers changing their growing practices.

- Turn off out-door lighting. Many insects will be drawn towards the lights e.g. moths. Insect navigation systems are disturbed by lights, consequently affecting their ability to feed.

- Get engaged in observing and counting insects through citizen science – you can help monitor insects to add to our scientific knowledge about population numbers by joining in initiatives which record insects e.g. the Wild Pollinator Count or Butterflies Australia.

References

1. Mata L. Anderson AN, Morán-Ordóñez A et al. 2021. Indigenous plants promote insect biodiversity in urban greenspaces” Ecological Applications 3 (4) e02309.

Regenerative Gardening = Sustainable Gardening

Some people say that the place to be in gardening is no longer just in sustainability - it’s being regenerative. But isn't that where SGA been all these years? We’ve been helping you learn how to improve your soil, your garden’s productivity, nurture the planet and produce food which will keep/make you healthy. We’re not changing the name of our organization to keep up this trendy buzzword, but let’s look at what regenerative garden enthusiasts mean by the term and how it relates to what SGA encourages gardeners to do.

What is it?

The concept of “Regenerative gardening” has evolved from a combination of sustainable/regenerative agriculture, agroecology, agroforestry, sustainable gardening with some permaculture thrown in. It is, however, unclear from where it first emerged i.e growing plants, feeding people, using the natural features of the land, water and nature in general to enhance productivity, minimizing harm to the environment and even making a positive contribution to it. Indeed, all these movements have drawn on observations of many of the ancient, traditional farming systems of indigenous peoples around the world.

Regenerative agriculture

According to the WA Landcare Network, farmers engaged in regenerative farming “have practised a holistic approach to land management that keeps water in the landscape, improves soil health, stores carbon and increases biodiversity.” It aims, thereby, to improve the quality of food grown on the land. An important means of improving the soil is to increase its carbon content which is sometimes referred to as “carbon farming”. Through soil improvement, soil biota will increase along with water-holding capacity. Such soil will produce more and better quality food leading to the concept of “food forests”.

A small, but increasing, number of farmers are practicing regenerative agriculture as they observe declining productivity and landscape degradation as a result of conventional farming methods.

Regenerative Gardening, Urban Agriculture and Food Forests

There have been many incentives for urban dwellers to establish local food production rather than rely on that which is commercially produced. Urban food production is occurring on land of various sizes ranging from balconies and roofs through standard house blocks, to many hectares of either public or private land. Among these incentives are:

- Higher quality, fresher fruit, nuts and vegetables

- Concern about environmental impacts on soil and water in conventional systems

- A desire to reduce food miles

- Increasing interest in plant-based diets rather than those based on animal protein - driven by attempts to reduce carbon dioxide emissions and inefficient use of soil and water resources as well as minimising harm to animals

- Concerns about chemicals used in agriculture and which are increasingly being detected in humans.

Characteristics of Regenerative Gardening and Farming

In the paragraphs below we have added links to pages on this SGA website which address these characteristics.

Learning from natural systems

Forests, grassland and other ecological communities maintain themselves by changes in their physical components or human intervention if not interfered with. In such ecosystems the physical components (landform, soil, water, air) work together to determine the living organisms (plants, animals, microbiota) and determine energy flows and nutrient cycles (https://www.sgaonline.org.au/garden-like-a-natural-farmer/ ). Although regenerative gardening or farming involve growing plants that are not indigenous to the area, attention to all other components is given, thus a more holistic approach is taken rather than just a focus on getting repeated production of a particular crop.

Minimal soil disturbance

This means not tilling or digging the soil so that its structure is maintained – i.e. spaces for air and water flows and for root penetration. This can be achieved by no-dig garden beds or no-till practices. In no-dig garden beds the growing medium is created by adding layers of soil, organic plant material and animal manures (https://www.sgaonline.org.au/how-to-make-a-no-dig-garden/). No-till means that after crops are harvested, the ground is not ploughed or dug, roots are left in the ground and weeds may be destroyed by solarization (see below). Another technique, soil aeration, using aerators – tools with prongs which punch holes – is still less damaging than ploughing or digging.

Sheet mulching

Mulches of either organic or non-organic materials are used between the planted crops to inhibit weed growth and retain moisture. They are also used to kill weeds and build soil on ground that has not yet been planted for crops (https://www.sgaonline.org.au/choosing-mulch-for-your-garden/ ). The materials are usually cardboard, newspaper, woodchips, straw or a combination. These all have the advantage of adding carbon to the soil and encouraging microbial growth. In small areas where perennials, not annuals, are grown, inorganic material can be used e.g. stones, but these do not add any nutrition.

Mulches of either organic or non-organic materials are used between the planted crops to inhibit weed growth and retain moisture. They are also used to kill weeds and build soil on ground that has not yet been planted for crops (https://www.sgaonline.org.au/choosing-mulch-for-your-garden/ ). The materials are usually cardboard, newspaper, woodchips, straw or a combination. These all have the advantage of adding carbon to the soil and encouraging microbial growth. In small areas where perennials, not annuals, are grown, inorganic material can be used e.g. stones, but these do not add any nutrition.

Crop rotation

Plants to be harvested or those in the same plant family, are not grown in the same area in the subsequent season. This minimizes the risk of host-specific pests and disease and also of excessive depletion of particular essential nutrients (https://www.sgaonline.org.au/crop-rotation/ ). There are many systems of rotation, some consisting of 4 cycles, one of which is a legume to add nitrogen to the soil. In other systems, and it may be many years before the initial crop is planted in the same place again.

Cover crops

Associated with crop rotation is the use of cover crops or green manures (https://www.sgaonline.org.au/green-manure/) . As in nature, soil is never left bare thus reducing weed invasion and erosion. Such crops are usually either grasses or legumes. Both add organic matter to the soil because root systems are left in place. They also prevent water runoff thus reducing erosion, increase biodiversity by attracting different insects and microbes from the previous crop and break cycles of host-specific disease. Crops with deeply penetrating roots can help break up compacted soil.

Legumes, so-called green manures, have the extra advantage of enriching the soil because of their nitrogen-fixing capabilities.

Cover crops are cut down or mown just before maturity and either left as surface mulch or lightly dug in.

Solarisation of weeds

Rather than pulling or poisoning weed-infested of grassy areas prior to planting crops, regenerative/sustainable gardeners cover the soil with either black or clear plastic with the edges held firmly in place (https://www.sgaonline.org.au/life-without-lawn/ ). Under clear plastic, weeds grow and cook in the heat. Black plastic minimizes growth by cutting off sunlight, but the plants still cook. As long as seed production has not occurred, remaining organic matter can be left in place to add to soil quality or it can be removed and composted.

Compost

Artificial fertilisers are not used and importation of manure is minimized. Rather, all organic waste from pruning, mowing or remains of plants after fruit/seed harvest are composted. Manure from on-site animals is an excellent addition to compost heaps. Mature compost not only minimizes waste but improves soil quality, fertility and structure (https://www.sgaonline.org.au/the-science-of-composting/ , https://www.sgaonline.org.au/creating-compost/) .

Perennials

Shifting focus from annual to perennial crops means that living roots are in the soil all the time, reducing compaction and erosion and providing host material and nutrition for soil microbiota. In addition to providing fruit or nuts, trees also are stable stores of carbon. Other such stores are vegetables which are perennial in the right climate.g. rhubarb, artichokes, asparagus, seakale, sorrel, breadfruit, sweet potato and many more. A new perennial relative of wheat, kernza, has been dev eloped and may be a promising alternative to annual wheat.

eloped and may be a promising alternative to annual wheat.

Natural Pest and Disease Control Rather than Chemicals

It is increasingly recognized that chemical use in plant systems often causes harm to beneficial organisms and tends to encourage development of resistance so that ever harsher chemicals are required. Regenerative agriculture and regenerative gardening rely on the natural ecosystem to keep pests and diseases under control. Natural systems are not monocultures, but complex arrays of plants and animals living in balance with one another. While such systems are not easy to create and harvest from in gardens or farms, it is possible to encourage biodiversity by using plants which mutually benefit each other through complementary nutrient requirements or production of helpful chemicals or to attract a range of beneficial insects and organisms which keep pests and disease under control. Such systems use companion planting (https://www.sgaonline.org.au/companion-planting/ ).

By utilizing all the above approaches soil is improved, the ecosystem is enhanced, carbon is trapped and productivity increases. What could be better?

Further Reading

https://www.onegreenplanet.org/lifestyle/build-regenerative-garden/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Regenerative_agriculture

Gardening Trends 2018-2019

Like many activities we engage in, gardening is subject to fashion and trends. So what are the current directions? Do they have anything to do with changing gardening’s impact on the planet? Or with healthy food production?

We consulted online articles from 12 different organisations which provided their analysis of garden trends for 2018 – 2019. We can identify 17 different trends, among them 9 were noted by 2 or more organisations. Although we present them as though they are part of a competition and allot them places, being a "winning" trend does not mean we endorse it or encourage you to follow.

The “Winning” Trends

1. Outdoor Rooms

Identified by six organizations, bringing features of the indoors to the outside is top of the list. Features to be included outdoors were comfortable soft seating, cooking facilities, fire-pits and sometimes even an area which is just like a room with roof and rain-and wind-proofing via zip-up plastic blinds.

2. Sharing 2nd Place

Five organizations noted these trends:

a. Edible Gardens

This type of garden is either in the form of dedicated vegetable patches (like that at the top of the page) or “foodscaping” i.e. including edibles among other plants for both their edible and decorative values.

b. Robo-Gardening

Robo-Gardening

A new term that indicates the use of technologies ranging from apps, drones, automatic watering systems and moisture detectors to motorized awnings, LED lighting and glow rocks.

3. Sharing 3rd Place

These trends were identified by four organisations.

a. Indoor Gardening

This takes the form of any style of indoor plant growing - ornamental plants in individual pots, jarrariums, edibles or herbs and even whole plant walls in restaurants. Apparently the share of revenue from indoor plant sales in growing nurseries has increased by 1.7% worldwide (The Age, 24-03-2019).

b.  Climate Change Gardens

Climate Change Gardens

Included in this trend are gardens that minimize water use by using drought-tolerant and resilient plants, that recycle both hard and soft materials, reduce chemical use and are extra low-maintenance.

4. Shared in 4th Place

These were noted by 3 organisations:

a. Habitat Gardens

These use native plants specifically to provide food and shelter for native birds and animals.

b. Home Sanctuary Gardens

Those that provide features to enhance contemplation and a peaceful atmosphere. They include water features and Zen gardens with raked stones and a few carefully placed plants or ornaments.

5. Sharing 5th Place

Two trends were identified by 2 organisations.

a. Texture

a. Texture

This is the use of a greater variety of textures in wall and ground treatments – pebbles, brick and sand combinations, wood and natural stone in combination, growing grass or other ground covers in between pavers and decorative mulches around plants.

b. More Attention to Plants than Hard Structures

There seems to be a tendency to give gardens their structure and contrast through different size and types of plant rather than using walls and hard features.

6. Eight other trends were identified:

Just one organisation listed these:

- Younger people (millennials) engaging in gardening

- Window Gardens – designed to be viewed through a window

- Topiary

- Unusual Features - painted rocks or sculptures and other ornaments

- Bright colours - either as flowers or furniture

- Concrete everywhere – from pavers, flooring, barbecues to even kitchen benches in outdoor rooms

- Swimming pools

- More professional design

What can we conclude?

Are we seeing a tendency to integrate more with the natural world? Many trends suggest that - outdoor rooms, indoor plants, more attention to plants in landscaping, greater focus on growing our own food, providing habitat and reducing impacts through climate change gardens.

But is having outdoor rooms that are just like indoors indicative of sustainability when they duplicate indoor facilities, waste resources and shut nature out? What about robo-gardening, concrete everywhere, bright unnatural colours and contrived artificial topiary – are they attempts to dominate nature for our own ends? Robo-gardening may, in the long run, reduce water use and make monitoring more efficient, but the use of electricity for motor-driven machines and other devices, tends to replace human energy and brain power with largely coal-fired power.

Maybe these contrasting trends are in different parts of our society – those who recognize they are part of the natural world and wish to be closer to it, protect it and reduce climate change and its impacts and those who wish to control it or who see it as threatening or too difficult to manage while they fulfill their personal needs.

At SGA we are delighted to see the trends towards eco-friendly gardening, waste minimization, water saving, wildlife protection and local food growing, especially among millennials who are now 29% of gardening households! We try to encourage these trends, provide the tools to do so and we depend upon you to do the same.

Are Plants Intelligent?

In the 1980’s, mentioning that plants could communicate or that they might be intelligent used to draw the response “Are you crazy?” when this was then proposed by scientists. Perhaps this reply derived from “hippy” suggestions that we should talk to our plants to make them grow better. But now there is solid evidence the plants can, indeed, respond to information in the rest of the world, respond to those messages in a variety of ways including sending messages to each other. The idea is emerging that the plant kingdom is a complex society in which members share information and subsequently respond, in a way similar to we do in human society, but using different languages1. Some scientists, therefore, suggest that plants possess intelligence2.

Plants show a number of behaviours that appear to be more than just a simple stimulus and response, but which involve communication both within and between plants. They respond to temperature, gravity, light, moisture, infections, concentrations of oxygen and carbon dioxide, predation, physical damage and touch. Let’s look at some of these in more detail.

Defending from attack

Early studies of willows, poplars and sugar maples showed that trees near those that were being attacked by insects started to release a range of chemicals which acted as repellents to those insects – somehow they “knew” that they were threatened by attack themselves. Others plants whose shoots were infected by disease, could release gases into the air which signalled the threat to plants close by so stimulating them to strengthen their own chemical defences. The gaseous chemicals released were different for different types of injury.

Some plants have more complex “behaviours”. For example, some whose roots were being attacked released gaseous substances which attracted nematodes which then killed the predator3. Others could interact with ants which protect them against attack by organisms which eat them, against disease and against competing plants4.

Some plants have more complex “behaviours”. For example, some whose roots were being attacked released gaseous substances which attracted nematodes which then killed the predator3. Others could interact with ants which protect them against attack by organisms which eat them, against disease and against competing plants4.

After hornworm attack, one species of the tobacco plant accumulated nicotine which blocked particular nerve receptors in other predators reducing their ability to attack the plant. Some of the chemicals used in transferring information between plant cells are the same as those found in humans.

When sagebrush plants were clipped they produced a gaseous chemical (methyl jasmonate) that stimulated neighbouring wild tobacco plants to increase their defensive biochemistry. These tobacco plants were then more resistant to subsequent attack by grasshoppers and cutworms5.

So would this mean that having a hedge, which we clipped regularly, near our veggie patch would reduce insect attack? An intriguing but, as yet, unproven possibility.

So would this mean that having a hedge, which we clipped regularly, near our veggie patch would reduce insect attack? An intriguing but, as yet, unproven possibility.

Ensuring reproduction

Plants have developed strategies to increase their reproductive chances. It was, in fact, Charles Darwin in the 1860s, who wrote that plants had “responded” to the characteristics of birds and insects so that their sexual organs were appropriately shaped to allow access for pollination3. These pollinators were then “rewarded” with nectar which was attractive to those pollinators and essential to their diets.

Some species of the Arum family produce a dung-like odour – exactly the same chemicals that are exuded from dung where the insects necessary for pollination of the Arum plants gather.

Nutrition

Most of us are aware that members of the Fabaceae (legumes such as peas and beans) “domesticate” the Rhizobium bacteria in nodules on their roots in return for supply of nitrogen which the bacteria can fix from the atmosphere. It seems too, that the Rhizobium bacteria produce hormones, cytokinins and auxins, which affect how the plant root behaves in growing to seek nutrients6.

Mycorrhiza as information networks

Perhaps even more interesting is how plants communicate through mycorrhizal networks. These are filaments of fungus that either penetrate the cells of plant roots, or sit on their surface. It is thought that 80 – 90% of plants have mycorrhizal associations7 and there are many tens of metres of filaments per gram of soil. These filamentous networks are better at absorbing water and nutrients than the plants themselves and thus they transport and exchange these compounds, increasing their absorption by plants up to 1000 fold.

They also facilitate sending “messages” between plants. Experiments have shown that bean plants infested with aphids can send signals to other plants when above-ground communication was blocked by physical barriers. The plants receiving the messages then produced chemicals which attracted other insects which were predators of the aphids8.

Nerve-like signaling within plants

It is well established that electrical as well as chemical signals are transmitted through plants in response to various stimuli such as damage. These signals seem to be via waves of reactive oxygen molecules and calcium ions. Although signaling in the nerve systems of the animal kingdom is mediated through potassium and sodium ion movement, the overall mechanism is similar9.

Very recent work from Australia researchers has shown that when plants are touched by humans, tools or even insects, their equivalent of an immune system is turned on and, because that uses plant resources, it can cause reduction in growth10. However, earlier research has shown that rubbing the leaves of can stimulate some plants defend themselves from fungal attack - also via this immune system-like pathway.11

Implications

Researchers are not claiming that plants have brains or can think rationally, but that they communicate in many ways that have similarities to human communication and intelligence. We should understand this if we are to both care for plants and benefit from them.

These studies provide a scientific basis for companion planting where certain plants have been observed to protect others from predation or disease. It’s not clear yet whether we might intentionally damage some plants, or plant sacrificial crops, in order that they alert others to strengthen their defences. But we should probably be gentle with the soil everywhere in gardens and forests so that the benefits of communication through mycorrhizal networks are not destroyed.

References

- McGowan K. 2013. How plants secretly talk to each other. Wired 12: 13.

- Trewavas A. 2005. Green Plants as Intelligent Organisms. Trends in Plant Science 10: 413-419.

- Baluška F, Mancuso S, Volkmann D (Eds.) 2006. Communication in Plants. Neuronal Aspects of Plant Life. Springer Verlag.

- Brouat C, Garcia N, Andarry C, McKey D. 2001. Plant lock and ant key: pairwise coevolution of an exclusion filter in an ant-plant mutualism. Proc R Soc Lond Ser B 268: 2131–2141.

- Karban R et al. 2000. Communication between plants: induced resistance in wild tobacco plants following clipping of neighboring sagebrush. Oecologia 125: 66-71.

- Castro O, Bucio J L. 2013. Small Molecules Involved in Transkingdom Communication between Plants and Rhizobacteria, in Molecular Microbial Ecology of the Rhizosphere: Volume 1 & 2 (ed F. J. de Bruijn), John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ, USA. doi: 10.1002/9781118297674.ch28

- Australian National Herbarium. 2013. https://www.anbg.gov.au/fungi/mycorrhiza.html

- Babikova Z et al. 2013. Underground signals carried through common mycelial networks warn neighbouring plants of aphid attack. Ecology Letters 16: 835–843.

- Choi W et al. 2016. Rapid, Long-Distance Electrical and Calcium Signaling in Plants. Annual Review of Plant Biology 67: 287-307.

- Yue Xu et al. 2018. Mitochondrial function modulates touch signalling in Arabidopsis thaliana. https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.14183

- Benikhle L., et al. 2013. Perception of soft mechanical stress in Arabidopsis leaves activates disease resistance. BMC Plant Biology13:133.

Greening Cities

Although beautiful old gardens are disappearing, there are initiatives to green cities. As old houses are pulled down to make way for new large ones, dual occupancies or apartment blocks built with very little garden and few trees, we sigh and wonder what the world is coming to. But Vision 202020, started in 2013, (now Green Spaces Better Places) was an attempt to increase green space in Australia’s cities so they can cope with a warming climate and pressures of modern living.

So far, there are 466 organisations in its network. Many government bodies, including local government, have signed up to it, are aligning their planning with it and are establishing specific projects to achieve this vision. Nationwide signatories include cities of Adelaide, Campbelltown, Ballarat, Central Goldfields, Canterbury, Melville, Fremantle, Gold Coast, Geelong, Stirling, Subiaco, Sydney, Vincent, Launceston, North Sydney, Penrith, Mundaring, Banyule, Darebin, Kingston, Melbourne, Yarra, Moreland and Whitehorse. Many other organisations, including 23 developer, construction companies have signed up along with many landscapers.

Why green cities?

There are many reasons to increase green space. See our previous article by Dr. Gregory Moore for more detail. Trees and other greenery moderate temperature and associated human comfort through shading, protecting from wind and through evapotranspiration. They also reduce glare and noise.1 These functions of vegetation lead to human health benefits such as reducing the cancer risk of sun exposure, reducing heat-related illness, improving mental wellbeing and reconnecting children with nature to improve their creativity and physical activity.

These benefits, in turn, flow on to economic benefits such as increased property values due to the aesthetics of trees and gardens, reducing costs of infrastructure and mechanical heating and cooling through shading and reducing health costs. A well-vegetated suburb has decreased costs of maintaining storm water systems because vegetation slows water flow and reduces soil erosion.

At least equally important are benefits to nature and ecosystems by absorbing carbon dioxide and providing wildlife habitat.

The big challenge

Urban green space has been decreasing since the 1980s. Then, houses typically took up 20 – 30% of house lots but by 2010 they took up at least 35-40%. So backyards shrunk from 150 square metres to an average of 100 square metres. This reduction in green space was not due to urban consolidation, but to growth of house sizes – in the 1980s it was an average of 161 square metres, but by 2012-13 it was 241 square metres – a 50% increase! This means that green space in suburbs is increasingly in the form of very narrow strips between and behind houses – spaces that are not particularly useful for growing canopy trees, providing wildlife corridors or for outdoor relaxation or children’s play.

Urban green space has been decreasing since the 1980s. Then, houses typically took up 20 – 30% of house lots but by 2010 they took up at least 35-40%. So backyards shrunk from 150 square metres to an average of 100 square metres. This reduction in green space was not due to urban consolidation, but to growth of house sizes – in the 1980s it was an average of 161 square metres, but by 2012-13 it was 241 square metres – a 50% increase! This means that green space in suburbs is increasingly in the form of very narrow strips between and behind houses – spaces that are not particularly useful for growing canopy trees, providing wildlife corridors or for outdoor relaxation or children’s play.

Progress so far

Most of the projects associated with Greener Spaces Better Places have involved research, data gathering, policy and planning. These include:

- A database which shows which plants grow best under what conditions

- Developing a simple soil testing kit

- Developing a straightforward process to bring together councils, residents and businesses to create a collaborative low cost composting program

- Projects associated with funding and investment such as how best to share risks and costs of creating more green space

- A directory of good design which showcases examples of creating or improving green space

- An approach to creating common green space when individual dwellings have little or none around them

- Expanding Permablitz so that more people and organisations can access methods of permaculture

- A process for creating a community action plan to involve more people

Is this just all talk and paper work?

It might look that way, but meeting the somewhat ambitious goal of 20% more green space in just 7 years requires development of innovative and clear approaches to getting the work done.

One of the most interesting projects is a workbook How to grow an urban forest. This was the result of collaboration of different levels of government. Aimed primarily at local councils, the workbook sets out 10 very clear steps. A key component is engaging the broader community, explaining why it is so important that there is more green space and enlisting their aid rather than just changing planning laws and planting trees on council-owned property. This book contains examples of cities that have started the process of greening.

What can gardeners do?

As gardeners seeking a more sustainable world, we are probably saddened as we see gardens engulfed by multiple occupancies and houses of monumental size. Do we really need such large houses? Can we convince State and Local governments to change planning laws that permit this gobbling up of green space by over-sized buildings?

As individuals, there are many things we can do:

- Create green walls and roofs. Research is advancing on the best plants, soil and growing conditions. An excellent example of such research is being conducted at the University of Melbourne, Burnley Campus (shown at right). Many businesses are providing systems to enable these for homeowners.

- Grow canopy trees

- Plant tall shrubs and creepers along fence lines and walls

- Replace hard surfaces with vegetation – grass and lawn alternatives work well for walkways and driveways. There are now systems for providing a rigid underlay for grassed driveways.

- Encourage family, friends and organisations to which you belong to green-up

- And, if you are politically-minded, you can approach your local council and support their initiatives to green your local area.

References

- Hall T. 2010. The life and death of the Australian backyard. CSIRO Publishing.

Carbon Emissions from Gardening

In a previous article we explored ways that gardeners can lock up carbon in the soil. Although increasing soil carbon is important, it doesn’t address ways of dealing with greenhouse gases that are talked about less often, namely, methane and nitrous oxide. Fortunately, the approaches to reducing emissions of these gases also lead to better soil structure and fertility.

Methane

This gas, with the chemical formula CH4, (i.e. each molecule contains one carbon atom) is worrisome because it is 25 times more potent than carbon dioxide in its global warming impact, weight for weight. However, it decays more rapidly in the atmosphere than carbon dioxide. It is produced naturally from wetlands and as a result of the digestive processes of ruminant animals (cows and sheep). It also leaks from natural gas systems.1

The major pathway for methane to be generated by gardening activities is through breakdown of organic matter in anaerobic conditions i.e. when oxygen is excluded. Gardeners may cause extra methane to be added to the atmosphere by some methods of composting and making weed “tea”, soil compaction and poor pond maintenance.

Composting

We all want compost, don’t we? But significant amounts of methane can be produced in the centre of compost heaps as material is broken down and the temperature rises. Methane production appears to be due to the density of the heap so that oxygen cannot penetrate and anaerobic microorganisms are favoured. To reduce this problem the heap needs to be well aerated. You can do this by:

Making your own compost bin or bay out of material that lets air through i.e. not solid plastic. Suitable materials are timber slats, logs or trellis or chicken wire.

Making your own compost bin or bay out of material that lets air through i.e. not solid plastic. Suitable materials are timber slats, logs or trellis or chicken wire.- Building the heap with a wooden pallet as the base. This gives some air space under the heap.

- Adding material such as straw that doesn’t get compacted so easily.2 Make sure that there are plenty of dried leaves, twigs and other fibrous materials in the heap. These are best added in layers with the amount of dry material about equal to the amount of wet/green.

- Including vertical aerating tubes as you build the heap. These can be made from tightly rolled chicken wire or PVC pipe with lots of holes drilled into it. Such devices have the added advantage of making it easy to get water into the centre a heap which is drying out.

- Using a tumbling device.

- There are a number of different designs for tumblers commercially available. If these are rotated every day or

so, they will aerate material satisfactorily. However, they sometimes lead to lumps which can get aerobic, if enough dry material is not added at the same or, indeed, mixed with the wet material before adding it. Actually turning the tumbler can be a problem since it can get quite heavy.

so, they will aerate material satisfactorily. However, they sometimes lead to lumps which can get aerobic, if enough dry material is not added at the same or, indeed, mixed with the wet material before adding it. Actually turning the tumbler can be a problem since it can get quite heavy. - For a thorough coverage of managing a tumbler see www.the-compost-gardener.com/composting-tips.html

- If all else fails, you can engage in some physical exercise and turn the heap regularly. You can do this with a garden fork (easier than a shovel), but it can be backbreaking work. There are various compost turning tools available now, such as one which looks a bit like a large corkscrew. It twists down easily and then you can pull out a plug of material from further down the heap.

Making weed “tea” under anaerobic conditions

Here is a dilemma. In a previous article we explored how to make compost, worm and weed teas to produce soluble fertilizer and discussed how the solid material needs almost constant stirring to avoid anaerobic conditions. We also pointed out that it may be easier for home gardeners to use the anaerobic method with only occasional stirring. Given that this method favours methane production, you might have a bit of a debate with yourself about the relative costs and benefits of each method or choose other ways of processing garden waste such as solarizing or composting.

Compacting soil

This happens by placing heavy weights on it e.g. heavy machinery or walking. Compaction removes the air spaces which aerobic microorganisms need for their oxygen supply. It is less likely to happen in raised garden beds and if the bed width is limited to about 1 metre so that you can reach across.

Pond Maintenance

Pond Maintenance

Ponds can become anaerobic if the water gets very murky or if the surface gets too much growth of water weeds such as Azolla3 as in the image on the right. These conditions can limit light entry so that submerged oxygenating plants are killed. Adding unsuitable fish species which stir up sediment can have a similar effect.

Nitrous oxide

Although it does not contain carbon atoms, nitrous oxide, N2O, is 298 times more potent as a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide, but is shorter lived, persisting in the atmosphere for 114 years. So we should not just think about carbon emissioins from gardening!

It has been calculated that 40% of emissions of this gas in the USA come from human activities with about 70% of that derived from agricultural land management. Nitrous oxide also happens to be the most important gas contributing to the hole in the ozone layer now that halocarbon levels are declining.

To reduce extra nitrous oxide being emitted we can:

- Use manures and other organic sources of nitrogen rather than synthetic nitrogen fertilisers and apply them carefully so that there is not excess nitrogen for plant use – that means not applying them when plants are not actively growing. Synthetic nitrogen fertilisers also contribute to making soil more acid.

- Since acid conditions encourage biochemical pathways that produce nitrous oxide, if soil pH is low we can add lime or dolomite.

- Use no-dig methods to avoid soil disturbance.

- Turn garden waste into compost or mulch rather than burning it.

- Avoid working soil when it is wet as this assists compaction which creates conditions in which soil micoorganisms convert nitrates to nitrous oxide.

References

- Reay D, Smith P, van Amstel A. 2010. Methane and Climate Change. London: Earthscan. ISBN978-1844078233.

- Sommer SG, H. B. Moeller. 2000. Emission of greenhouse gases during composting of deep litter from pig production – effect of straw content. 2000. J. Agricultural science 134 (3) 327-335.

- Rachel A, Janes JW, Eaton K . 1996. The effects of floating mats of Azolla filiculoides and Lemna minuta Kunth on the growth of submerged macrophytes. Hydrobiologia 340 (1) 23-26.

Compost, Worm and Weed Teas

If you are a gardener who tries to reduce your impacts on the natural environment, you will be using methods which avoid manufactured fertilisers, pesticides and herbicides and which minimize waste. So you’re into composting and worm farming and mixing the resulting solid material into the soil. However, at many times of the year a liquid fertilizer in the form of a “tea” may give plants, especially vegetables and fruit trees, a boost that is quicker than applying the manure, worm castings or compost which release their nutrients much more slowly. Such teas can be made from compost, weeds and other greenery and manures. How do you make and use them? What are their pros and cons?

The advantages of using teas are said to be:

- They provide nutrients for you plants more quickly in the soil than the solid material used to make them.

- The microbes in them make soil nutrients available and help prevent soil and plant diseases, something that commercial fertilisers do not do.

- They are cheaper than commercially manufactured fertilisers.

- Unwanted plant material in your garden can be turned into something really useful.

- They make the garden more self-sufficient by recycling material it has produced.

On the other hand, because the effect of teas depends on the quality of the starting materials, how the teas are made, the climate, when they are applied, the plants they are used on and the state of the soil before their use, there is debate about their usefulness, with some findings that they can be harmful.

Extracts and teas

Don’t confuse extracts and teas. The simplest, but not the best, method of making a liquid fertiliser from your garden material is to make an extract. This is made by covering some compost, worm castings or manure with water for a few hours or days. Nutrients and minerals from the solid materials dissolve in the water and microorganisms present on the solids can enter the liquid. This can then be used by either applying directly to the soil or, when diluted to the colour of weak tea, as a foliar spray. However, these extracts are inferior to teas which have been brewed.

Why bother making a tea?

If properly brewed, teas provide much more than minerals and other nutrients. They are also very rich in microorganisms, a mixture of bacteria, fungi, protozoa and nematodes, which can fight plant disease-causing organisms in the soil and on foliage and can convert soil nutrients into forms that can be taken up by plants. They usually take longer to make than extracts and may involve more effort. For many gardeners and organic farmers, making compost tea is both a science and an art. And there are many different opinions about what method is best and, indeed, whether they work at all.

Compost tea

To prepare compost tea, put mature compost into a container like a bucket or plastic rubbish bin. You can put compost straight into it or into a “bag” which can be made from a piece of shade cloth or other material with small holes like old net curtains, stockings of panty hose. Cover the compost with water. It is preferable to use rain water, filtered water or mains water that has been allowed to stand for 24 hours to allow the chlorine to off-gas before adding to the weeds. The removal of chlorine makes it easier for microorganisms to multiply. You will need to add something to start the process off by providing easy to access nutrients for microbial growth. The best additions are brown sugar or molasses but others could be some fish meal, some canned fish which has been allowed to “go off”, grain meal, fish food, rotten fruit, compost, garden soil or finished compost. Nitrogen rich vs sugar rich additions give different results in terms of favouring bacteria or fungi.

Then there are two ways you can brew the tea:

Aerobic

This requires aeration. This process provides oxygen which allows aerobic microorganisms to multiply rapidly and break down the plant material. You could use a stick, which means you will need to stir it several times a day for about 10 days. In between stirring, cover the bucket or bin loosely so that air can enter. But unless you really like physical exercise and can remember to stir each day, using a fish tank aerator for about 3 days is a good alternative. There are many websites which provide ideas for you to make your own compost tea aerator, and there are even some commercially available assemblies.

Tea made this way will not smell unpleasant and should be used straight away. There are different opinions about how long the tea should be brewed. It really depends on your compost, the temperature and the nature of aeration. At some point, aerobic microorganisms will have used available nutrients and not be getting enough oxygen, so anaerobic microorganisms will take over. At this stage it will start to smell wiffy – but don’t despair. You can use it quickly before the aerobic microbes all die (because there will always be a few aerobic microorganisms) or let it go on brewing under anaerobic conditions.

Anaerobic

Some practitioners recommend that it might be better for home gardeners to use the easier anaerobic method which does not involve aerating and favours microorganisms which do not require oxygen. Just cover the container fairly firmly and wait for about 3 weeks. It requires longer and tends to be smellier but still produces a useful product. Some say that after the anaerobic microbes have finished, aerobic ones will take over again. But as I indicated, there is some controversy over this.

Worm tea and worm farm leachate

Most of us are also familiar with the liquid that comes out of the worm farms – called names such as worm wee, worm juice or worm tea, but really is a leachate. It contains plant nutrients, but is not rich in microorganisms like compost tea. Worm leachate really needs to be used cautiously since it contains “bad” bacteria as well as “good” and may be harmful to plants, especially if it smells “off”.

For worm tea, the castings from a worm farm can replace compost in the teas described above.

Weed tea

Weed tea

The best weed tea is made from plants with deep roots like comfrey, dandelion and nettle since they have incorporated minerals that have been leached from topsoil. Making weed tea is also a great way of extracting nutrients from plant material you don’t want in either your garden or in your compost heap where they would start multiplying. It also includes plants with runners and those which take root easily.

Follow the methods described for compost tea but it may be necessary to weigh the weeds down between stirring because they may float.

Manure tea

Animal manure can be used to make a tea by the same methods as for compost tea. However, there is a high risk of producing a brew which contains organisms which can be harmful to both plants and humans, especially if it is anaerobic. An extract, however, is a quick way making a nutrient-rich solution, but it will not have the same benefits as a microorganism-rich aerobic tea.

Using teas

Remove the bag which contains the solids and let it drain into the container. Or if you haven’t used a bag, pour the liquid through some shade cloth or other fine material laid in a soil sieve. It would be wise to do this wearing rubber gloves (and perhaps a peg on your nose!) since this might be a pretty potent and smelly brew. Put the solid material into your compost heap where it will break down further.

Remember, teas contain living organisms and should be treated with respect. Sun and heat can kill them, so apply them to the garden early in the morning or after dusk. The most useful times of the year to use them appear to be early spring, several times during the growing season and towards the end of autumn so that the organisms can work in the soil over winter.

Handle the brews carefully with gloves and don’t apply to vegetable leaves that will be eaten, especially if anaerobic and smell bad, since it is possible that pathogenic organisms are present. Use the tea diluted one to ten as a foliar spray, or less diluted if applying to soil.

And don't expect miracles - results depend on so many factors that they are impossible to predict. We'd be interested in hearing of your experience.

References

Lowenfels J and Lewis W. (2010) Teaming with microbes. Timber Press, Portland, Oregon.

What are the Benefits of Aerated Compost Teas vs. Classic Teas? https://faq.gardenweb.com/faq/lists/organic/2002082739009975.html

Secrets of Making Compost Tea.www.compostjunkie.com/making-compost-tea.html

Gift Ideas for Sustainable Gardeners

If you're like me, come the beginning of December, I'm scratching my head to think of suitable presents that might be appreciated by the recipients. Even if I'm giving to someone who isn't really a gardener or not particularly interested in sustainability, it feels better to give something that I know is not just going to add further pollution to the world, but something that might improve it a bit. So here are some ideas - some are more suitable as gifts for avid sustainability devotees, but others could be given to anyone.

Gardening Gifts

Recycled planter

Although an obvious gift for a gardener is a plant of some sort, why not make it more special by supplying it in a container that is made from something recycled and is also decorative. It could be something simple and home made, as in the image on the right or it could be something more decorative and perhaps bought from a store.

Although an obvious gift for a gardener is a plant of some sort, why not make it more special by supplying it in a container that is made from something recycled and is also decorative. It could be something simple and home made, as in the image on the right or it could be something more decorative and perhaps bought from a store.

Seeds

Avid gardeners welcome seeds, particularly heirloom varieties, for more than their unique traits. Heirloom seeds, obtainable from specialist seed suppliers, play a crucial role in fostering genetic diversity, preserving older genetic types. Plants grown from these seeds yield fertile seeds, allowing continuous cultivation over successive years. Beyond practicality, heirloom plants often deliver superior flavour, making them a choice not only for preserving the past but also for cultivating a more vibrant and flavourful future garden. You could even save seeds from your own heirloom plants, put them in attractive packets which you could also make yourself out of recycled paper - there are templates and instructions on various websites.

There are newer seeds being marketed by some seed suppliers arise from cross-breeding of 2 different varieties to yield plants with particular characteristics e.g. colour or vigour. SGA does not recommend using these. If seed from that type of plant is saved and subsequently sown, there may be no offspring at all, or, if there are, the offspring will not be like the parent plant. In contrast, plants grown from heirloom seeds will produce fertile seeds which can be saved and used to grow the same plant in subsequent years. So gifts of such seeds are gifts that “last” years.”

Plant Labels

Gardeners need to identify what seeds they have planted in either pots or in the ground. A great gift would be a set of these made from either plastic or wood. Perhaps accompanied by a weather-resistant marker pen.

Watering Can

In my experience, watering cans can wear out, especially if they are left outside or used a lot. Some can rust or the the screws attaching the handle can fall out. Plastic watering cans suffer from sun damage and have a limited life. Most gardeners find that having more than one is very useful. Look out for good quality examples or those that are decorative. Or you could paint designs on one yourself.

Insect hotel

These creations, also called insectaries, provide somewhere that beneficial insects can shelter in the garden can serve as a garden decoration as well. If you don't know about them see our article which also shows some different designs. You could make one like the example on the right, yourself - from a strip of heavy duty fabric e.g. shade cloth, with pieces of hollowed out wood packed inside. Bamboo is a useful material since it already has hollows, but it is easy to drill holes in other materials. Providing insect shelters like this are a great way of keeping control of the nuisance bugs.

There are also designs that provide shelter from harsh weather (wind and rain) for butterflies. They usually have long vertical slits instead of round holes.

Such "hotels" are also available commercially - just do a web search. But it is worth reading up a bit on good design and materials to use. Since SGA's article was written, these "hotels" (also called insectaries) have become quite popular and there is some excellent online advice on how to maximise their insect-friendliness.

Nestbox

Nestbox

Shelter for bigger critters could also make an excellent gift. They can offer places for birds, microbats, ringtail possums or sugar gliders. There are different designs for the different animals and birds. You'd best check out what creatures are in the area and, of course, if the recipient want those creatures in their garden. Check out some advice here.

Compost bin or worm farm

Since compost bins or worm farms are excellent ways of turning waste into "black gold" for the garden, they make wonderful gifts. Of course, check first if your recipient has one already.

Tools or Clothing

There many garden tools which gardeners need. Giving them as gifts mean you can buy higher quality than gardeners might for themselves:

- secateurs

- lopper for difficult pruning branches thicker than those that secateurs can cut

- a really lovely and long lasting stainless steel hand trowel or hand fork

- long lasting scratch-proof garden gloves

- pruning saw

- knee pads that strap on

- too carrier - either a tool belt/apron to wear around the waist or a caddy to carry.

SGA Gifts