Pesticides most harmful to bees

Pesticide use is one of the factors which may be affecting bee populations worldwide. Since much of our food production depends on pollination by bees, whether bee populations have been declining globally has been the source of concern – and some confusion. While there have been reports of declining bee numbers it is now thought that these are the result of local population changes and declining species richness i.e. of particular species of bee. As well as pesticide use, the cause of such declines could result from the virus carried by the Varroa mite, climate change or habitat loss, or a combination of all four factors. In Australia, we now need to pay more attention to the threat of pesticides since, with the detection of Varoa mite in Victoria in 2018, honeybee populations are more threatened. So here we look at the pesticides most harmful to bees. We might immediately think “neonics”, but while it is true that these are toxic for bees, there are many others which kill both honeybees and native Australian bees.

In SGA’s app WiseGardening – Choices to Protect You and the Planet, where we rate risks of chemical pesticide products, we have included the full range of products in garden use. Five hundred and twenty seven products out of the 869 reviewed so far have either moderate or high risks to bees. There are 304 with high risk and 223 with moderate risk. Of those 527 products with moderate or high risk to bees, there are still 318 commercially available and 209 have been discontinued. Of those currently available, 181 are high risk to bees and 131 are of moderate risk.

Neonicotinoids (Neonics)

As the name suggests, these chemicals are similar to nicotine and they react with the same nerve receptors in nerve junctions as nicotine does. This enables them to cause paralysis and death. They are more toxic to insects than they are to mammals and birds.

Acetamiprid

Clothianidin

Dinotefuran

Imidacloprid

Nitenpyram

Thiocloprid

Thiamethoxam

These chemicals have an advantage as insecticides because they are water-soluble and, if sprayed on the soil, plants can easily take them up. In theory, this reduces the risk of unwanted effects on beneficial insects caused by broadscale spraying and consequent spray-drift. However, their solubility means that they can enter and be stored in pollen and flower nectar, placing pollinators such as bees at risk. These soluble chemicals are also very toxic to aquatic organisms when excess enters waterways. Searching for these chemical names in WiseGardening reveals products containing them and their risks.

The Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA) which regulates pesticide standards states “All neonicotinoids registered for use in Australia have previously been through the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA)’s chemical risk assessment process..” A review of neonicotinoids started in 2019 is still in progress. Neonicotinoids are some of many pesticides which are permitted in Australia but banned overseas e.g. in UK and EU. Although some neonicotinoids are available for farming use, many retailers have withdrawn them for sale for household and garden use.

Organophosphates

These chemicals have been widely used in the past because of their effectiveness against a variety of pests. Because they are extremely toxic neurotoxins and have high persistence in the environment many are now banned. Perhaps best known is DDT used widely against mosquitoes – it is now withdrawn from sale.

Most are now banned overseas, but products containing malathion, chlorpyrifos, dichlorvos and diazinon are commercially available in Australia - mostly as dusts, and powders to control lawn beetles, grubs, slaters, termites and ants. Some are in fruit fly traps or pest strips which don’t carry quite so much risk since they are not sprays which can disperse. However, because of their persistence, residues can be picked up by bees. Although most products containing organophosphates are now discontinued, some still lurk in garden sheds and garages. When you search WiseGardening. for the chemical ingredient names you will see that they pose high risks to a variety of organisms, including humans.

Pyrethrins

These are a family of products, some natural and others synthetic, and include permethrin, cypermethrin, bifenthrin, phenothrin and deltamethrin. Many of us think that products containing pyrethrin or something that sounds similar, are natural and, therefore, safe. But this is not the case.

There is confusion about terminology of pyrethrin (natural) and pyrethroids (synthetic). The latter are particularly toxic to bees. They affect the nervous system by changing activity of nerve sodium channels. They are more effective on insects because they have greater affinity for insect nerves and are active at the lower temperatures of cold-blooded insects in comparison to warm-blooded mammals.

There is confusion about terminology of pyrethrin (natural) and pyrethroids (synthetic). The latter are particularly toxic to bees. They affect the nervous system by changing activity of nerve sodium channels. They are more effective on insects because they have greater affinity for insect nerves and are active at the lower temperatures of cold-blooded insects in comparison to warm-blooded mammals.

A search on WiseGardening reveals a large number of commercially available products containing pyrethrins which pose high risks to bees and other organisms. If using these products, avoid spraying during the day when bees are active and wait until bee-attracting flowers are no longer present. Since pyrethrins are not persistent in the environment, the effects of residues wane after about one week.

Fipronil

Like the above chemicals, fipronil affects nerve systems but by changing the activity of the chloride channels. It was introduced to the market in 1996, predominantly to control indoor insects (e.g. moths and fleas), spiders and rodents. It can affect mammals and humans, but only at much higher concentrations.

In WiseGardening, 16 commercially available products containing fipronil and one which is discontinued have high risks for bees, birds and mammals and moderate risks for fish and earthworms.

Sulfoxaflor

A relatively new pesticide based on sulfoxaflor was released in the USA in 2013 and subsequently in Australia. It is one of many pesticides which are permitted in Australia but banned overseas e.g. in UK and EU Currently, it appears to be only available for agricultural and horticultural use and not in gardens.

Other chemical ingredients toxic to bees in pesticides in Australia

Apart from those chemicals discussed above, there are many other pesticides available for use in horticultural and agricultural industries which contain ingredients which are toxic for bees. A list of those known in 2014 is here.

What you should do

What you should do

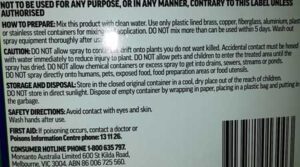

Many of us try to avoid chemical pesticides altogether. But that is not always possible when a whole crop of lovingly-grown fruit or vegetables is being attacked. So consult SGA’s WiseGardening app and, as we point out, PLEASE READ PRODUCT LABELS with respect to guidelines for use. But don’t just rely on the product label because those labels do not show toxicities to the full range of organisms covered in WiseGardening.

Soil as a Carbon Store

Rather than regarding soil as just a medium for growing plants, we should also be viewing soil as a carbon store. This means that it is an important resource for reducing CO2 levels in the atmosphere. Clearing of forests and intensive agricultural use, which paid little attention to soil quality by relying on artificial fertilizer use, have led to extensive degradation of our soils Australia-wide.

This view of soil is, however, gradually changing. New research indicates that minimizing soil disturbance could reduce the impacts of agriculture on climate by up to 30%.1 While the area of land devoted to agriculture is much larger than that used as gardens across Australia, gardeners can learn from the agricultural experience and play a role in addressing climate change.

Avoid disturbing soil

When soil is tilled or dug, its structure is disturbed so that large air pockets are formed which fill with oxygen. This stimulates soil microbial life to convert the carbon and oxygen to CO2 which then escapes to the atmosphere. In undisturbed soil, there are fewer air pockets. These are formed as a result of earthworm activity and root growth but still provide enough drainage and root growth. Although there are other gases produced in soil, such as methane and nitrous oxide, they have a higher warming potential than CO2. Studies have shown that overall carbon storage in undisturbed soil was greater than if it had been tilled1. So, to keep carbon in soil, the aim is to keep oxygen out.

Decomposition of plant and animal material leads to many different chemical compounds and in different physical forms. Soil carbon can be solid organic particles, bound to minerals or dissolved in water2. Studies have shown that the carbon bound to minerals remains in soil longer, and also contains nitrogen compounds. In fact, carbon in soil is needed to nourish microbes which help to create fertile soil3. Getting the right mix of different types of carbon in soil is complex, but the key is to avoid digging or tilling to minimize CO2 loss to the atmosphere.

What happens to plant material after harvest

Of course, if growing food crops, an important question is what to do with plant material that is left after harvest. One approach, which SGA has described is to use it as green manure. The conventional method has been to dig it in. However, although digging in enriches soil in organic matter, it leads to CO2 release. In order to avoid this,  alternatives have been tried:

alternatives have been tried:

- Cutting off plant material above the ground and letting what is left die off. This works for plants which die naturally. The next crop is then planted in between the residues.

- Covering plant material that is left after harvest with black plastic or tarpaulin to prevent light entry thus killing remaining roots and yet warming the soil. This allows soil microbes to break the organic material down and store it. After removal of the covering, the next crop can be planted.

These approaches have also been explored from another point of view – that is, how to minimize artificial fertilizer use, yet promote fertility, avoid soil degradation, enrich the soil and enhance food security. This approach has been termed “ecological intensification”4. It utilizes the soil’s natural ecosystem consisting of a large variety of microorganisms - tens of thousands consisting of fungi, bacteria and viruses, as well as other larger organisms. It is now thought that much of soil carbon is not the remains of degraded plant material, but actually dead bodies of microorganisms which consumed it.

The message for gardeners

With increasing emphasis on urban agriculture to supply food locally, gardeners in both home and community gardens can use the two techniques describe above to avoid digging and to obtain many benefits – for storing carbon, and other plant nutrients for building soil, increasing its fertility and reducing our own labour inputs. in brief:

- Avoid digging

- Keep ground covered with organic material

- Let soil microbes process plant waste after harvest

- Sow or plant directly into left over plant material from previous growth.

References

- Cooper HV, Sjögersten S, Lark RM, Mooney SJ. 2021. To till or not to till in a temperate ecosystem? Implications for climate change mitigation. Environmental Research Letters, Volume 16, (5)

- Lavallee JM, Soong JL, Francesca Cotrufo M. 2019. Conceptualizing soil organic matter into particulate and mineral-associated forms to address global change in the 21st century. Global Change Biology https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14859

- Wallenstein MD. 2022. To restore our soils, feed the microbes. https://theconversation.com/to-restore-our-soils-feed-the-microbes-79616

- Bommarco R, Kleijn D, Potts SG. 2013. Ecological intensification: harnessing ecosystem services for food security. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 28 (4), 230-238.

Controlling Mosquitoes Sustainably

Controlling mosquitoes sustainably in gardens is a challenge now that many parts of eastern Australia are experiencing such high rainfall. Conditions for mosquitoes to breed are ideal with so many pools of water, large and small, in mild to warm weather conditions1 and climate change is causing an extension of their range from the tropics to sub-tropical and temperate areas2. Controlling mosquitoes with chemical sprays pollutes the environment and is not the way to go since, in the long run, this only leads to them evolving to resist those chemicals.

Why are Mosquitoes a Problem?

Mosquitoes bite and feed on the blood of animal species such as humans, horses and cattle, as well as birds. Not only are mosquitoes annoying because of the itching resulting from their bites, but they spread disease. Some diseases such as Barmah Forest virus, Murray Valley encephalitis, dengue fever, Japanese encephalitis and Ross River virus are currently found in Australia3,4. Of concern is that these diseases might occur further south than their current ranges due to the combination of increased rainfall and rising temperatures.

How to Protect Yourself and Others

Remove standing water

Any persistent water can act as a breeding ground and harbour the larvae (wrigglers). So

Any persistent water can act as a breeding ground and harbour the larvae (wrigglers). So  either empty these reservoirs or remove them from where they can collect water. They include, watering cans, jars, bottles, tanks, buckets, jerry cans, bird baths and saucers under pots1.

either empty these reservoirs or remove them from where they can collect water. They include, watering cans, jars, bottles, tanks, buckets, jerry cans, bird baths and saucers under pots1.

Ponds and puddles cannot be easily removed, so other methods are needed (read on).

Repellents

Scented plants

Many scented plants act as repellents e.g. lavender, marigold, lemon grass (citronella), catmint, rosemary, basil, scented geranium (citronella), bee balm, mint, floss flower (Ageratum), sage, alliums (garlic, onions etc), yarrow and fennel. Growing those in your garden would be helpful.

Personal repellents

There are a number of commercially available chemical repellents that can be placed on your skin. They are available as creams, wipes, sprays, aerosols and in wearable devices such as wrist bands. The most effective contain diethyltoluamide (DEET), picaridin (odourless) or oil of lemon eucalyptus. Care is recommended with DEET since some people are sensitive to it, reacting with skin irritations, nausea or headaches. Tea tree oil is also useful.

Others

Vapour dispensing units can be used inside dwellings. Outdoors, mosquito candles or colls which burn natural oils such as lemongrass, citronella, peppermint and other oils mentioned above, can be used. These are, however, not specific for mosquitoes and may harm other species.

Barriers

Clothing

Wear long, loose fitting and light-coloured clothing when outside. Mosquitoes are attracted to dark colours and shady areas. Shoes should be closed - don't wear sandals..

Screens

Screens

Cover all windows, doors, vents, and other entrances with insect screens. Where commercial screens cannot be obtained, netting fixed firmly over the apertures is effective.

If sleeping outdoors, bed nets are helpful.

Behaviour

Since mosquitoes are less active in daylight, avoid being outdoors during hours between dawn and dusk.

Predators

Fish which eat mosquito larvae are very useful if added to ponds or dams. Australian native fish suitable for garden ponds are the Murray rainbowfish Melanotaenia fluviatis the crimson spotted rainbowfish Melanotaenia duboulayi and the Southern Blue-eye Pseudomugil signifer (also known as the Pacific blue-eye). They survive best north of the Goulbourn river in Victoria. For areas further south, the Australian smelt Retropinna semoni do well in ponds and do not pose a threat to frogs or tadpoles. Other fish like the pygmy perch or galaxias are available sometimes, but the pygmy perch can attack tadpoles5.Do NOT ADD NON-NATIVE FISH such as Gold fish, Guppies, Koi, Tilapias to water bodies since, although they also eat mosquitoes, they are invasive species which can deplete native fish numbers by either predation or depleting food sources

Do NOT ADD NON-NATIVE FISH such as Gold fish, Guppies, Koi, Tilapias to water bodies since, although they also eat mosquitoes, they are invasive species which can deplete native fish numbers by either predation or depleting food sources6Aquatic Invaders

Destruction by Other Methods

Pyrethrins derived from the natural sources can be sprayed to kill mosquitoes. However, pyrethrins are toxic to other insects as well so they need to be used carefully, preferably after dark when other insects are not so active. See our WiseGardening app and search for “pyrethrin” to see the risks to humans and other species of sprays containing pyrethrin.

Mosquito larvae can be killed or prevented from maturing by some commercially available products. There are liquid drops which coat water surfaces and can be applied to bodies of standing water. Another is BTi (a variety of Bacillus thuringiensis) which contains bacteria that infect and kill larvae. It is currently only available in large packs. Both products appear to be safe to humans and other species.

Methods NOT Recommended

Devices such as zappers or traps which attract mosquitoes with light and/or carbon dioxide will kill mosquitoes, but also kill other insects. General chemical insecticides have a similar disadvantage. When you search our app WiseGardening for “mosquitoes” you will see that even those listed specifically for mosquitoes carry moderate risks for other species.

The Future?

Given current climate and weather predictions, we will be facing more instances of long term changes in the natural environment resulting in threats to animal and human health due to disease vectors like mosquitoes moving south. More and more we need to recognise how interlinked humans are to the world around us and how we need to take care of it.References

- Forsyth JE, Mutuku FM, Kibe L, Mwashee L, Bongo J, Egemba C, et al. 2020 Source reduction with a purpose: Mosquito ecology and community perspectives offer insights for improving household mosquito management in coastal Kenya. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 14(5): e0008239. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0008239

- Reiter P. 2021. Climate Change and Mosquito-Borne Disease.. 2001. Environmental Health Perspectives•VOLUME109 |SUPPLEMENT1. Pp. 141 – 161.

- Takken W, Verhuls NO..Host Preferences of Blood-Feeding Mosquitoes. Annu. Rev. Entomol.. 58:433–53.

- Mosquito-borne disease. 2022. https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/mosquito-borne-diseases

- Native Fish Australia 2022.https://www.nativefish.asn.au/

- Aquatic Invaders Identification Guide. 2012. https://www.fish.wa.gov.au/Documents/biosecurity/introduced-pests-guide-freshwater.pdf

What to do for Flooded Gardens

What to do for flooded gardens is, unfortunately, a question more people need to ask. It seems that our climate is making extreme rainfall and subsequent flooding more likely in some parts of the country. For gardeners this is a heart-breaking experience on top of the damage to homes and other possessions, but for those whose gardens have been flooded, some caution is needed. We summarise here advice from research institutions specializing in agriculture, horticulture and arboriculture on how to manage flood-affected gardens.

How Floods Affect Gardens

Floods can kill plants or severely damage them by:

Floods can kill plants or severely damage them by:

- Erosion of soil so that roots are exposed. This makes trees more susceptible to uprooting in subsequent winds.

- Water logging, silt deposition or compaction removing oxygen from soil spaces around plant roots. This can also destroy microbial life that is essential in soil to provide nutrients for plant growth

- Making roots more susceptible to root-rot organisms

- Contamination from run-off from roads, farms and industry, sewage and other chemicals from transport vehicles and household products. These may include heavy metals such as cadmium, arsenic and lead, pesticides and other hazardous chemicals from industry such as oils

- Buildup in soil of decomposition products such as ethanol, carbon dioxide and methane

- Prevention of photosynthesis by water or silt coverage of leaves

- Removal of bark from tree or shrub trunks from impact of debris in rapidly flowing water

- Insect infestation resulting from damage to trunks may further weaken trees and shrubs.

On the other hand, river plains that are affected by floods and properly managed after the flood are among the most fertile areas for many crops. Here the emphasis must be on appropriate management!

General Garden Recovery from Flood

Initially do nothing! Difficult as that may be, trying to remedy garden damage before soil has dried out sufficiently can do even more damage.

Don’t:

- walk or dig since these actions cause more compaction and disturbance of soil structure. Wait until water has drained and dried enough so that soil is firm enough to stand on without sinking in.

- prune plants whose leaves are wilting as soon as waters have subsided. You may be surprised as some slowly recover.

- add fertilizer since stressed plants will not take it up and subsequent rains my wash it away.

What you can do:

- Allow sufficient time to assess tree and shrub damage. They may lose leaves or branches may be broken, but remove only obviously dead branches.

- When walking on soil after flood waters have subsided, be aware of risks of standing on or touching debris such as broken glass or nails which could cause injury.

- Wear gloves and closed shoes which should be removed before entering any dwelling to avoid spreading contamination. And wash hands thoroughly after removing gloves

- If lower leaves of non-produce plants that covered in silt, try hosing it off – maybe even using a pressure hose. Although adding more water to the garden sounds peculiar, leaving silt on leaves will inhibit block sunlight, inhibiting photosynthesis which plants need to perform in order to survive.

- It may be useful to add fungicide since wet warm conditions after floods can stimulate fungal growth.

- Add commercially available soil microbes and organic matter to the soil surface. If you use fungicide, wait a week before adding microbe preparation. They will help the natural soil biota which are so necessary to breakdown organic sources of nutrients and for preventing both human and plant disease.

Can I Eat Produce from a Flooded Garden?

Since flood waters carry contamination of various sorts, including toxic chemicals and pathogenic bacteria (e.g. E. coli, Salmonella) or parasites, which affect food safety, you will, unfortunately, need to discard some produce or delay planting again. Appropriate action depends on the type of produce and the degree of exposure to the waters.

Fruit or vegetables that have come into DIRECT contact with flood waters

These should be discarded if they have been submerged or been splashed by the waters. Some research organisations suggest that if the produce has only been splashed, you could wait 72 hours before harvesting, then thoroughly clean and cook it before eating it.

However, some produce that has been splashed is particularly risky e.g. those with soft surfaces e.g. leafy greens, berries, tomatoes, eggplants, peppers or melons, and should not be consumed.

It is wisest to discard root crops like potatoes and carrots. Crops like rhubarb or asparagus should be dealt with in the same way. However, the University of Wisconsin-Madison and West Virginia University suggest that root crops may be salvaged by cleaning first with drinking water, then bleach and rinsed again with water ( see those website for details).

Whether submerged or only splashed, no produce should be eaten raw.

No produce that has been exposed should be preserved by any method because preservation processes are not guaranteed to remove or destroy contamination.

When handling any produce from a flooded garden make sure to prevent cross-contamination by washing hands thoroughly with soap for 30 seconds between dealing with different types of fruit or vegetables.

Produce that Floodwaters Have Not Touched

There are slightly different opinions about how long you should wait to eat produce that matures after flood waters have receded and were never in direct contact with the waters. Estimates of between 90 – 120 days are if the produce is peeled and cooked. Make sure that it is completely intact with no cracks, holes or bruises – such produce should be discarded.

Planting Next Season’s Edibles

It is advised not to sow or plant after the flood until at least 2 months have elapsed. For fruiting plants like tomatoes, wait 60 days, but for root crops like radishes wait at least 100 days. During this time adding organic matter to the soil would be useful.

This might be a good time to install raised garden beds to reduce the chance of edibles being affected in subsequent floods.

References

https://extension.umn.edu/planting-and-growing-guides/how-manage-flood-damage-trees

https://www.purdue.edu/hla/sites/yardandgarden/after-the-flood-garden-and-landscape-plants/

https://polk.extension.wisc.edu/2020/06/30/flood-waters-entered-your-garden/

https://hmaaustralia.com.au/flood-garden-recovery/

Warrigal Greens

Warrigal greens Tetragonia tetragonioides are an edible Australian native groundcover. This bushfood is a member of the family Aizoaceae and is related to marigolds and figs. It is also native to New Zealand and countries around the Pacific rim, sometimes referred to as New Zealand spinach or Botany Bay spinach. Its Australian name comes from the Aboriginal word “warrigal” meaning wild or wild dog and the scientific name reflects its 10-sided seeds.

Growing naturally in all parts of Australia except the Northern Territory, it is a leafy ground cover spreading to around 1.5m. It can be seen growing between rocks near beaches, on sand dunes and in estuaries and is tolerant of wind and salty soil1.

Its leaves are fleshy and triangular with tiny green-yellow flowers between the leaf base and the stem2.

The particular requirements requirements for growing in gardens seem to be depend on the original source of seeds – if from a sandy area, then it will tolerate more soil with a higher sand content or if from cool to temperate regions it will be more tolerant of cold.

Planting Schedule

This useful vegetable can be grown from both seeds and cuttings.

Warm areas: March - April (seeds in trays), May - June (seedlings)

Temperate areas: March - April (seed in trays), May - June (seedlings)

Cool to cold areas: January - February (seed in trays), April - May (seedlings)

Seeds will grow directly in the soil if it is not too hot or too cold. It is best to soak them in warm water overnight before sowing.

It is a perennial in temperate - warm areas, but an annual in cooler zones.

Position, Position, Position

It will grow in full sun or part shade.

Talking Dirty

This plant is fairly adaptable, tolerating pH 5.8-7.5 and a range of soil types from sandy to clay as long as it is moist and free draining.

Invasiveness?

Because it has long trailing stems which root fairly easily and self-seeds it can be quite invasive. If that is as problem for, then it can be grown in pots with the leafy stems left to trail. However, its readiness to grow and shallow roots makes it a useful ground cover under fruit trees. If grown under shrubs it will be quite happy to climb.

Because it has long trailing stems which root fairly easily and self-seeds it can be quite invasive. If that is as problem for, then it can be grown in pots with the leafy stems left to trail. However, its readiness to grow and shallow roots makes it a useful ground cover under fruit trees. If grown under shrubs it will be quite happy to climb.

However, its enthusiastic spreading habit makes it a good choice to cover problem areas and minimise weed growth. And at the same time it provide a reliable source of food.

Feed Me!

Mature compost or a little well-rotted manure is all that is needed.

What about the Water?

Keep soil moist as its shallow root system means that it will struggle in dry conditions.

Are we there yet?

These plants are quick growing, so after planting seedlings you will be able to harvest leaves in around 10 weeks.

Pests and the Rest

Although a remarkably disease resistant plant, it can succumb to mosaic virus and some fungal diseases.

Slugs, snails and caterpillars may take an occasional nibble but they don’t seem to be all that keen. Root knot nematode, aphids, two-spotted spider mite have occasionally been observed, but overall it is fairly pest-resistant.

Eat Me!

The leaves make a wonderful spinach substitute, but stems are not edible. Leaves are high in vitamins A, B1, B2 and C3 and fibre as well as anti-oxidants4. They have a mild taste, but since they contain high levels of oxalic acid, they should be blanched before eating i.e. 1 – 2 minutes in boiling water.

They can be used hot in soups and stir fries or cooled and added to salads. They benefit from some added acid such as vinegar or lemon juice and are given zing by spicy dressings.

References

- Watkins CB, Brown JMA, Dromgoole FI. 1988. Salt tolerance of the coastal plant, Tetragonia trigyna Banks et Sol. Ex Hook. (climbing New Zealand spinach). New Zealand Journal of Botany 26: 153-162

- Australian Native Plants Society (Australia)

- Samuelson J, Drost D. New Zealand Spinach in the Garden. Utah State University Horticulture Extension.

- MA Lee, HJ Choi, JS Kang, YW Choi, Joo, Woo-Hong. 2008. Antioxidant activities of the solvent extracts from Tetragonia tetragonioides. Journal of Life Science 18 (2) 220-227.

Myrtle Rust is a Spreading Problem

Myrtle rust is a spreading problem in Australia. It is a fungus, Puccinia psidii, which affects plants in the family Myrtaceae.

While there are several species overseas, there is only one in Australia Austropuccinia psidii1. It was first seen in the central coast of NSW in 2010 and has since spread along from southern NSW to far north Queensland along the east coast of NSW. It is also in Victoria and Tasmania, Melville Island and the Northern Territory. It is in found in plant nurseries, private gardens, parks, reserves and plant nurseries.

This fungus is of special concern because, as well as being a problem in gardens, it is a threat of severe damage and even extinctions to the many Australian natives species which are members of the Myrtaceae family important in many native ecosystems. By 2020, 382 species were known to be infected 2.

Plants Affected

The NSW government states that the following plants are susceptible:

- “Eucalyptus species

- willow myrtle (Agonis flexuosa)

- turpentine (Syncarpia glomulifera)

- bottlebrush (Callistemon species)

- paperbark (Melaleuca species)

- water gum (Tristanis neriifolia)

- tea tree (Leptospermum species)

- lilly pilly (Syzygium wilsonii)” 3

Myrtle Rust also infects exotic ornamental plants e.g. myrtle, plants with edible fruit e.g. feijoa and guava and others used for spice e.g cloves and allspice.

How Does it Spread?

Fungal spores can be borne by insects, animals (including humans), wind and water. They can be carried several kilometers by these means, but much further if transported on contaminated clothing, plants, vehicles or equipment. Germination of spores requires dampness, low light or darkness and mild temperatures (15 – 25°).

What Does It Look Like?

A few days after infection, bright yellow “dots” appear on leaves, flowers, fruits and shoots 3. The fungus penetrates plant cells to obtain nutrients and spots turn brown or grey causing leaves become brown and die (see image at top of this article). This may result in stunted growth and badly affected plants may die.

Control

There are severe impacts of myrtle rust since as well as affecting ecosystem integrity there are economic, social and cultural values. It will affect nursery and garden industries, regional industries including indigenous, recreation and tourism. This has led the Australian government to develop a National Action Plan (2). This plan seeks to raise awareness and to enable response to the threats by assessing impacts, addressing biosecurity issues and facilitating recovery.

Gardeners and land managers can take a range of actions to control this fungus. However, some may not be practical or possible depending on the size and number of infected plants or those likely to become infected. These possible actions are:

Prevention

- Become familiar with what myrtle rust looks like

- Remove plants that are likely to become infected

- Do not move plants that are infected

- In high- risk areas, launder clothes, hats and gloves after working with any plants

- inspect plants on a regular basis for any signs of myrtle rust – this includes plants which might be being considered for purchase. This is especially important in mild damp conditions in spring and autumn and, in some locations, in summer

- Disinfect tools and any equipment used - including mobile phones and glasses.

Dealing With Infected Plants

- Unfortunately, there is no real alternative to spraying with a fungicide since any attempt to remove infected

plants inevitably involves risk of further spread. This should be done several days before trying to take any of the following actions

plants inevitably involves risk of further spread. This should be done several days before trying to take any of the following actions - Enclose infected small plants in plastic bags before sending to landfill

- If plants are large, chop them into smaller pieces and place in plastic bags. It is best to store such bags in a sunny location to solarize them which will destroy spores. Then send bags to landfill

- DO NOT PLACE ANY INFECTED PLANT MATERIAL, EVEN IF SOLARISED, IN GREEN BINS FOR COUNCILS TO TAKE AWAY!

Spraying With Chemicals

It is unusual for SGA to recommend using chemicals, but they are currently necessary to address the growing myrtle rust problem.

There are several fungicides registered for use with myrtle rust. It is best to seek advice from your local nursery about these. Like all chemicals, such fungicides have impacts on other species, so to help you make a wise choice, acquaint yourself with them using the SGA app WiseGardening which provides details.

References

- Australian Government. Department of Agriculture, Water and Environment. 2021.

- Makinson RO, Pegg GS, Carnegie AJ, (2020) Myrtle Rust in Australia – a National Action Plan, Australian Plant Biosecurity Science Foundation, Canberra, Australia. 2020.

- NSW Government. NSW Department of Industry. Myrtle Rust. 2022.

Gardening and Food Security

Availability of sufficient food is an issue for many around the world. If you are reading this your food supply is probably currently quite secure. Even if you don’t grow much of your own food, the fact that you have email, a computer, time to garden and probably the money to buy seeds and other gardening requirements means that you are not worrying about feeding yourself or your family. However, this is not the case for an increasing number of people, not just in the developing world.

Food security means that people are able to meet their dietary needs and food preferences at all times.It means people are getting fresh, healthy food in adequate amounts to maintain personal health and wellbeing. The federal government’s website on food security states that access to food in Australia places it among the top 5 countries and that 60 million people could be fed from what we produce. Currently, Australia exports more than half of the food it produces and over 90% of fresh produce available to us is produced in Australia. If food security is an issue, enough is either not available or, increasingly, these days, is not affordable.

Future of Australian food security

A report from the Prime Minister’s Science, Engineering and Innovation Council in 2010 stated that “food security is an issue for Australia” because of many challenges:

- An increasing population.

- Decreasing productivity growth of primary industry.

- Increasing land degradation and urban expansion into productive land.

- Climate variability and vulnerability to climate change.

- Increasing dependence on imports of food and products involved in its production which can be affected by events in other countries such as conflict.

- Long transport chains which are of a “just in time” nature and which can spread food contamination quickly and which contribute many food miles to Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Future Directions International, a not-for-profit strategic research institute which researches issues facing Australia is concerned about food security. It concludes that Australia’s food security will increasingly depend on local urban agriculture i.e. food production on urban land in the form of community gardens and home gardening. Urban agriculture is prominent in African and Latin American cities and is slowly increasing in Europe and Australia. Motivations in developed countries, so far, are mainly to obtain chemical-free fresh food rather than addressing food shortages. A survey in 2013 showed that 48 per cent of urban households produced some of their own food. In Melbourne and South East Queensland, government plans recognize a need to increase urban capacity to produce fresh food locally.

They note, however, that there are a range of risks associated with inexperienced and untrained people growing food. SGA will examine these risks and how to overcome them in a subsequent article.

Current food insecurity

Although most of us can prepare for future food insecurity or are already providing significant amounts of food for ourselves, this is not the case for all. The federal government estimated that 2% of our population experience food insecurity and that in some risk groups it could be up to 24%. These groups are socially disadvantaged through lack of, or insufficient, employment to meet family needs, chronic illness, frailty, disability or social or physical isolation. Such groups may also lack knowledge, skills or facilities to prepare or store food.

What is being done about this?

Food Distribution Organisations

A number of not-for-profit organisations are dedicated to sourcing and distributing food to those who cannot provide it for themselves. They provide food for 644,000 people annually including 216,000 children. A worryingly large number of people are not able to be provided for.

Foodbank is the largest of these organization, providing 166,000 meals per day. They rescue surplus edible food from manufacturers, retailers and farmers by collecting it and taking it to warehouses. The food is then collected by more than 2,500 charities and 1,500 schools who distribute it as hampers or prepared meals. Since much food is seasonal or is available unpredictably Foodbank is working with manufacturers to supply staples such as breakfast cereals, tinned fruit and vegetable, pasta and sauce. This type of partnership relies on donations of money and of ingredients, packaging and transport from suppliers and manufacturers.

FareShare supplies 25,000 free cooked meals from rescued food or donated food with the help of 800 volunteers. Much of the ingredients are fresh, or freshly made and have unpredictable supply. Therefore the kitchen needs to rapidly develop recipes to use them quickly in appetizing meals. The organization has a kitchen garden program, run by volunteers overseen by a horticulturalist, to produce vegetables on vacant unused land. FareShare is always looking for more fertile land and donations of everything involved in food gardening, from tools and gardening clothing to seeds and seedlings.

FareShare supplies 25,000 free cooked meals from rescued food or donated food with the help of 800 volunteers. Much of the ingredients are fresh, or freshly made and have unpredictable supply. Therefore the kitchen needs to rapidly develop recipes to use them quickly in appetizing meals. The organization has a kitchen garden program, run by volunteers overseen by a horticulturalist, to produce vegetables on vacant unused land. FareShare is always looking for more fertile land and donations of everything involved in food gardening, from tools and gardening clothing to seeds and seedlings.

SecondBite is similar to Foodbank and distributes 20,350,000 kg food around Australia annually. Supermarkets, markets, farmers, caterers, wholesalers and events donate surplus food. The organization is supported by the goodwill of participating businesses, volunteers and financial donations.

Individual Action

The above organisations are usually only able to collect large quantities of food e.g. around 50Kg. But you could:

- Make an effort to grow at least some of your favourite vegies, herbs and, space permitting, fruit. Just about all of us can grow something, so give it a go this year. You’ll save money, and you’ll be making a difference.

- Start or join a community garden and connect with others in your community. connected, food secure community is a fantastic place to live.

- Save seeds from your plants, especially those that are heirloom or heritage, and grow them yourself, share with friends or take to a Harvest Swap.

- Join or start a Harvest Swap to establish a network of gardeners who are producing food at home.

- Donate your excess produce or pantry content to organisations such as those below:

Organisations that Gardeners can Participate in

Your local church or school might have drop-in lunch/breakfast programs which welcome donations of food.

New initiatives are arising to share excess produce at a local level e.g. the innovative Food is Free Laneway, Ballarat which is a bit like a Food Swap except you don’t need to bring anything to be able to take. Similar sharing venues now exist in 15 different locations.

New initiatives are arising to share excess produce at a local level e.g. the innovative Food is Free Laneway, Ballarat which is a bit like a Food Swap except you don’t need to bring anything to be able to take. Similar sharing venues now exist in 15 different locations.

In North West Tasmania, Produce to People collects food from farmers, food suppliers and backyard gardens and gives it to neighbourhood houses, schools and charities.

A social enterprise program which supports the homeless with a focus on youth, STREAT runs cafes, a coffee roastery and catering business which provides opportunities for youth to be trained in hospitality. It works with charities to support youth in other ways. A new project is developing a high-end café and kitchen garden – they welcome donations of fresh food, seeds and seedlings.

Quercus Community Kitchen Garden, established by SGA with support of the Helen McPherson Smith Trust, grows food which, along with food from the Albury/Wodonga FoodShare, is used in the local Community Food Project. This project prepares meals from fresh food and freezes and stores them for weekly distribution to people unable to meet their food needs.

A different Food is Free project started in Austin, Texas, where people are making their front gardens or other spare pieces of land available to grow vegetables and fruit for others.

So to alleviate food insecurity you can get involved in any this type of organisation - or set up your own!

Worm Farms and Composting - Radio Interview

Our Training and Learning Coordinator discusses how to start and maintain worm farms and compost heaps.

|

Garden Trends in 2021

Garden trends in 2021 are rather different from in 2020 since, although growing food is still prominent, there is an increased focus on raised garden beds and creating pleasant living spaces.

Trends develop in response to how people are interacting with their physical and social environments and are a process of innovation and copying. Last year the advent of COVID-19 initiated a trend to start gardening partly because people were required to stay at home and partly because of fears of running short of food. In 2021, we still have COVID, but there has been a drift to gardens spaces to live in as well as to be productive.

We have analysed 7 online gardening magazines and blogs in both northern and southern hemispheres and found 31 so-called trends. Since many were related to others we have assembled them in 9 main themes so that you can see if you are part of a trend or a non-conformist or even a rebel.

Major Themes

Sustainability and Growing Food

This theme is mainly about food production, mostly vegetables rather than fruit, as well as raised beds, sometimes in quite formal arrangements, to optimize growth. It includes composting, worm farms, organic methods, water conservation, permaculture methods, mulching, growing local native plants and trees for shade. An example is from Better Homes and Gardens. Associated with this were planting nectar-rich flowers to attract birds and pollinators such as bees and providing habitat for them. Recycling or repurposing items into the garden, such as using an old heating coil as a water feature, are other aspects under the general heading of environmental sustainability.

This theme is mainly about food production, mostly vegetables rather than fruit, as well as raised beds, sometimes in quite formal arrangements, to optimize growth. It includes composting, worm farms, organic methods, water conservation, permaculture methods, mulching, growing local native plants and trees for shade. An example is from Better Homes and Gardens. Associated with this were planting nectar-rich flowers to attract birds and pollinators such as bees and providing habitat for them. Recycling or repurposing items into the garden, such as using an old heating coil as a water feature, are other aspects under the general heading of environmental sustainability.

Another aspect of this trend has been articulated by Paul Bangay, celebrated Australian gardener, is a greater use of succulents, many of which have interesting flowers and attractive growing forms. They can be used to advantage in a warming and drying climate since they need little water.

Rewilding, Mixing Flowers, Herbs and Veggies and Romantic Cottage Gardens

This trend combines a number of factors:

- more natural, wild appearance

- colourful landscapes of wildflowers

- habitat and food source for bees, other pollinators, butterflies and birds by planting nectar-rich flowers

- a “cottage” style with vegetables and herbs together with flowers

These gardens have roses and lavender among the vegetables, vines and creepers over fences, fields of colourful annual wild flowers and grasses. Associated with this is creating Instagram-friendly images.

Paul Bangay says that shaping shrubs is becoming softer using the natural shape of the shrub as a guide.and less like the neatly clipped hedges which have previously been fashionable, Westringeas and Correas are well suited to this approach. Australian native plants are also increasingly being mixed in with other types.

The Garden as a Living Space Flowing from Indoors

As gardening became a more prominent activity during lock downs, we have been spending more time outdoors at home, wanting it to be accessible and comfortable. So a lot of attention is being paid to having direct connection from indoor living areas to both garden beds and paved areas with furniture to relax and entertain.

A part of this theme is small gardens created on balconies or courtyards where people can relax among the plants.

A part of this theme is small gardens created on balconies or courtyards where people can relax among the plants.

Another aspect is bringing more human comfort and protection from sun and wind to the garden in the form of gazebos and canopies. And even positioning hot tubs on the lawn among the shrubs.

Single Colour Themes

Most frequent colour is white for flowers, walls, furniture and even shed. This colour is possibly chosen because of the large array of white flowering plants to choose from.

Grey gardens also feature where shrubs, herbs and ground covers with silver/grey foliage dominate. Garden furniture in grey tones is also popular.

Interesting Containers and Indoor Plants

Continuing previous trends is the interest in indoor gardening using exotic warm-climate plants as features, to clean the air and to provide some relaxing green to boost well-being. Unusual, stylish containers are also the rage.

Windowsill gardens are favorites with apartment dwellers who want to be part of the gardening trend. This location is often the only place with sufficient sunshine and light to grow herbs and annuals.

Textures and Patterns

Creating paved areas with mixed colour tiling to achieve patterns, sometimes in Mediterranean style, is increasing. Other examples are walls where patterned designs are created using bricks or wood blocks. Use of rattan in furniture is another way of adding geometric pattern and texture.

Buying and Learning Online

With restrictions on travel, buying plants online has increased dramatically and will possibly continue to some degree now that we recognize its convenience. Also popular are online gardening workshops and videos, especially for those just starting gardens and needing to learn the basics.

Involving Kids

Almost essential for young families during COVID times is finding ways of engaging children in acts of creating and maintaining vegetable gardens. Also important is using gardens to provide opportunities to entertain the little ones by, for example, going on bug hunts.

Novel Plants

There is more interest in plants that have not been widely grown. There is a move to seek herbs other than parsley and rosemary, such as lemon thyme, lovage, tarragon, stevia or French sorrel. More attention is also being paid to succulents and colourful exotics to grow indoors such as cordyline, bromeliads and begonias.

Minor Themes

Less dominant themes include a move towards topiary, but choosing and building pizza ovens instead of barbecues outdoors.

References

Banner Image: https://www.idealhome.co.uk/news/instagram-top-10-emerging-garden-trends-for-2021-254890

Plastic in the Garden

How do we reduce use of plastic in the garden even though it is so useful? Unfortunately, it is polluting and causes much environmental damage. Although many councils recycle plastics, most do not permit garden pots in recycling bins and have either special collection points for them or you must seek out an independent pot recycler.

But it is not just pots that are a problem, there are other items used in gardens that are made of plastic and must also be considered.

Why recycle plastic?

Even those seemingly solid and recyclable polypropylene plastic products produce materials that find their way into oceans where they are a growing pollution problem. When most common plastics break down they form microplastics and drift far way into surface ocean swirls where they are ingested by fish and end up in the food chain eventually into animal flesh which humans and other organisms eat1.

What is the difference between biodegradable and compostable plastic?

Many pots and other plastic products are now manufactured to be either biodegradable or compostable. But those two words do not mean the same thing, so don’t confuse them even though they plastics labelled with either are able to be broken down into their constituent chemical components. But the processes for that happening are different and yield different results2.

Compostable materials will break down into humus IF they are in a situation where the composting process can take place i.e. temperature, moisture, oxygen and presence of microorganisms are just right. They create rich soil and they will not result in long-lasting microplastics.

Biodegradable products will break down naturally, even in landfills in the absence of oxygen – given enough time. However, toxic components may still be present3.

So, if we need/want to use plastic, it is better for the planet if we choose compostable plastics if they are available.

Alternatives

To be even more sustainable in the garden, we can seek out alternatives to plastic:

Fabric and other “eco-friendly”pots

Watch out for so-called biodegradable or eco-friendly products. However some, like certain grow-bags are made from plastics like polypropylene which is derived from fossil fuels3. Unless such products are “certified compostable” they will not completely break down. Instead look for pots made from coir (coconut fibre) or manure. There are also compostable pots made from peat but SGA does not recommend all of these since peat may be obtained from endangered peat bogs.

However, remember that all these pots are manufactured for a single use.

Long lasting pots

Old plastic pots

There are a number of things that can be used many times over and old pots can be re-used many times if they are properly cleaned between uses. This re-use reduces the overall load of plastic on the environment. Such pots can frequently be found in local waste collections, but make sure you sterilize them before use.

Pots made from other materials

Pots made from other materials

Try pots made from wood fibre, porcelain, clay i.e. terracotta, or old wooden barrels (as long as they are not made from fresh new wood) .

SGA’s supporters have supplied us with a range of ideas for upcycling old household material including old boots and kettles.

Other Garden Items

There are alternatives for other garden items that are commonly  made of plastic. This is particularly so for furniture where timber and metal and glass are less polluting alternatives. SGA reviewed those here.

made of plastic. This is particularly so for furniture where timber and metal and glass are less polluting alternatives. SGA reviewed those here.

Other ideas for avoiding or recycling plastic:

For growing from seed:

-

-

-

- Egg containers

- Yoghurt pots and other plastic containers that have contained food purchased from supermarkets. Just drill or punch holes in the base.

- Containers from supermarkets for berries. They have holes already in them. Just put some paper that was destined for the recycling bin on the base to prevent soil from escaping - water will drain through. And since they have lids with holes, they also serve as mini-greenhouses.

-

-

For labelling pots:

- Paddlepop sticks – use soft black pencils to write. The sticks can be re-used by removing the writing with a rubber.

- Old plastic spoons or knives which have been lying around - write with waterproof pen.

If we use our imaginations, there are so many ways that we can reduce plastic in the garden!

References

-

- Michael Gross. ScienceDirect ( 2015) Oceans of Plastic. R993 – 96

- https://www.oceanwatch.org.au/uncategorized/compostable-vs-biodegradable/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biodegradable_plastic

Using Phosphorus Sustainably in Gardens

It is widely known that root vegetables need phosphorus to grow well, but is it so widely known that phosphorus supplies may be dwindling and that phosphorus fertilizer is a major cause of waterway pollution? Using phosphorus sustainably in gardens, in agriculture and forestry is becoming much more important.

Importance of Phosphorus to Life

Phosphorus is one of those chemicals that are basic building blocks of life. It is essential in DNA, RNA, the phospholipids that are part of the wall of every plant or animal cell and is in adenosine triphosphate which carries energy through living systems.

While it is essential for growth of all plants1, it is particularly required by root vegetables. If you read articles about growing them e.g. carrots2, you will see that it is recommended to add phosphorus fertilizer, in contrast to leafy greens where the recommendation is to add nitrogen. This is especially important in Australia where soils are low in phosphorus3.

While it is essential for growth of all plants1, it is particularly required by root vegetables. If you read articles about growing them e.g. carrots2, you will see that it is recommended to add phosphorus fertilizer, in contrast to leafy greens where the recommendation is to add nitrogen. This is especially important in Australia where soils are low in phosphorus3.

Phosphorus in soil is present in both organic and inorganic forms, but only the inorganic form, phosphate, is it available to plants1. Since releasing phosphate by microbes is a slow process, farmers have traditionally added materials which are already rich in phosphate. Initially guano (bird droppings) was a phosphorus source and then in the mid-1800s, when this source became limiting, sedimentary phosphate-rich rock became the major source. It can be used as rock dust as a slow release fertilizer, but liquid phosphate fertilizer is obtained by acid extraction of the source material.

Phosphorus Supplies

All but around 10% of phosphorus use worldwide is within the food chain4. Already by 2010 it was predicted that world phosphorus supplies would last only another 80 years assuming the then population. But as human numbers are increasing, the supplies would not last that long.

These considerations led to the idea of “Peak Phosphorus” being reached by around 20305 . However, much debate has followed and it is recognized that this peak really only represents economically available phosphorus because, although there are more phosphorus-containing rock deposits, accessing them becomes too expensive. Additionally, 84% of these are held by only 5 countries6 but exploration continues for others.

The shortage is mainly because modern agricultural production is a one-way process in which fertilizer is added to soil, excess fertilizer applied to soil is washed into waterways and crops are consumed by animals including humans with waste excreted into sewage. This process is not only wasteful but creates waterway pollution leading to oxygen depletion which affects aquatic life including the killing of fish7.

How Can We Ensure Future Phosphorus Supplies?

It is time for “reduce, reuse, recycle”!

Reduce

Minimise Use

This can be done by adjusting fertilizer application to just that needed by crops. Universities are developing tools to help farmers do this accurately. Getting the phosphate levels just right is not so easy for gardeners, although kits are available, so we recommend making sure the soil is enriched with compost and manures rather than adding extra phosphate.

Scientific approaches have been developed using pigs for which phosphorus is an essential dietary component for them to grow well. An enzyme, phytase, which breaks down organic sources of phosphorus, can be added to their diets so that they need less phosphorus supplementation7. Even a genetically modified pig has been developed which produces the enzyme itself. Both approaches can reduce phosphorus in the food industry8.

Plant Modification

Research on genes that control phosphate transfer within plants may lead to breeding plants better adapted to low phosphate levels9.

Reuse and Recycle

Reversing the one-way pathway of phosphorus is essential. That really puts the focus on turning all organic waste into material that can be added to soil. In traditional practice, before the advent of manufactured fertilisers, all material produced farm was kept on the farms. So composting and using animal and human excrement was the norm. However, using either urine or faeces is associated with risks of disease caused by pathogenic microorganisms on harvested food or just from working the soil.

Urine is the largest source of phosphorus in cities and their surrounds 6 So methods for extracting phosphorus from urine and wastewater are being developed and there are some commercial products being tested. These involve the formation of a different form of phosphorus called struvite which actually preforms better than the form commonly used. It is, however, more expensive.

Solutions for Sustainable Gardening

- Make as much compost as possible from food and garden waste. Phosphorus concentrations are, however,

low and release is slow.

low and release is slow. - Add manures or wood ash phosphorus but release is also slow.

- Keep chickens and use debris from their run which contains their manure.

- Grind or crush fish and chicken bones, boil them and cut them into smaller pieces when they become soft and add them to soil.

- Add clay particles to soil as it helps prevent free phosphate from being washed away.

- Use a commercially available form of organically certified phosphorus. These include rock dust, bone meal and kelp products.

In any case, it is vital that we save as much phosphorus-containing material that is “waste” from our food and gardens.

No matter whatever additions you use, it is important that the soil pH is between 6.0 and 7.0 so that phosphorus becomes accessible to plants1.

- https://web.mit.edu/12.000/www/m2016/finalwebsite/solutions/phosphorus.html

- https://www.globalnetacademy.edu.au/grow-better-root-vegetables-by-adding-phosphorus-to-your-soil/

- https://www.publish.csiro.au/cp/Fulltext/cp13135

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peak_phosphorus#Estimates_of_world_phosphate_reserves

- Prud'Homme, M. (2010). Peak Phosphorus: an issue to be addressed. Fertilizers and Agriculture, International Fertilizer Industry Association (IFA). February 2010.

- https://theconversation.com/thats-a-relief-we-have-a-way-to-recover-phosphorus-from-our-urine-117751

- https://theconversation.com/how-the-great-phosphorus-shortage-could-leave-us-all-hungry-54432

- https://www.popsci.com/science/article/2010-09/greener-bacon/

- https://theconversation.com/scientists-work-to-solve-phosphate-shortage-the-dwindling-resource-required-

- https://www.aces.edu/blog/topics/crop-production/understanding-phosphorus-forms-and-their-cycling-in-the-soil/to-grow-food-120390

What Gardeners Can Do About Climate Change

Are you wondering what gardeners can do about climate change? Gardening and agriculture produce several greenhouse gasses apart from carbon dioxide – and we can help lower emissions of most of them. Even if each gardener can only decrease small amounts of them, every bit counts!

Scientists have been warning about the warming climate for the last 30 or more years, but it has taken a long time for governments to recognize that it is occurring. Those of us who are close to our gardens and the land have seen the effects already happening such as fruit ripening earlier or not at all because there was not enough winter chill.

In Australia both the CSIRO1and the Bureau of Meteorology2 have issued reports in 2020 showing that temperatures have increased by 1.4 degrees Celsius since 1910 with most warming occurring since the 1950s. They also describe what we are expecting in the future, including increases in dangerous fire weather days, ocean warming and acidification, less snow and more changes in rainfall patterns with increasing intense events.

While we must adapt to the coming changes, we need to be taking action NOW to try to slow the rate of global warming that is causing these changes. Gardeners can help!

Increase Vegetation Cover

We all know that Landcare groups have been planting trees for many years to prevent erosion on degraded land. Fortunately, these plantings also help take up carbon dioxide from the atmosphere – as long as they become permanent carbon sinks. However, the rate and amount of greenhouse gas removal by trees is not as high as the emissions from use of fossil fuels, so very large areas of land need to be devoted to forests3.

Gardeners can help by planting as much vegetation as possible – even lawn helps! However, if you live in a bush fire prone area take care with the location and type of trees or shrubs.

Gardeners can help by planting as much vegetation as possible – even lawn helps! However, if you live in a bush fire prone area take care with the location and type of trees or shrubs.

Reducing carbon emissions can also be achieved by avoiding concrete in paving and walls since it creates high greenhouse gas emissions in its manufacture. And don’t forget green walls and roofs! Not only do they add more plant cover, but they add insulation to buildings, so reducing energy use in heating and cooling.

But although these actions are important, there is much more that gardeners can do!

Reduce Use of Fertilisers

It is being increasingly realized that nitrous oxide produced when nitrogenous fertilisers break down in the soil makes a significant contribution to global warming – nitrous oxide is around 300 times more powerful than carbon dioxide as a warming gas and around 10 times more powerful than methane.

Of course, the bulk of such fertilisers are applied as synthetic products and manures in agriculture to cropland and pasture and nitrous oxide is also produced from the chemical industry, wastewater treatment and fossil fuel burning. But gardening uses them too.

We can reduce the polluting effect of these fertilisers by:

- matching levels of application to the actual needs of plants,

- applying them in slow release form

- rotating leguminous crops, which produce their own nitrogen, with other crops.

- using as many natural growing methods to improve productivity by improving enhance soil quality.

Although compost or worm castings/ tea from your own green/food waste are not rich in nitrogen, they have the benefit of not requiring fossil fuel use and, therefore, having relatively low carbon emissions.

Manures from your chooks or collected from farms will still cause nitrous oxide emissions but they cause less release of carbon dioxide than commercially sourced manures which produce carbon emissions through their transportation. Other organic products such as blood and bone, fish meal, seaweed extract, compost and natural minerals e.g. organically certified phosphorus are less energy-intensive than chemical fertilisers that have gone through complex extraction and manufacturing processes.

Composting

Sending organic waste to landfill results in methane production because decomposition occurs in the absence of oxygen. In contrast, composting it, either at home or commercially, reduces methane production and, although aerobic composting in your compost heap produces some carbon dioxide, application of the finished product to soil helps soil to retain carbon as well as increasing its fertility.

Biochar

Biochar is charcoal derived from the burning of plant material in the absence of oxygen. This creates a stable form of carbon rather than releasing carbon dioxide to the air by natural decay processes. It has become slowly more popular over this century for that property and also its capacity to benefit plant growth. When added to soil it improves its structure, helps retain water and provides a surface for beneficial soil microbes and fungi which help plants take up nutrients. It also creates a stable form A number of years ago, SGA published an article reviewing biochar and indicating how gardeners can make their own. Now it is produced by several commercial companies and is sold by a range of garden centres and other retailers.

Pest Control

Using integrated pest management techniques and companion planting rather than manufactured products to control insects, weeds and disease also reduces carbon emissions. These alternative approaches minimize the need for such products which require energy-intensive, carbon-dioxide emitting processes in their production and transportation.

Modify Our Diets

Many people are now realizing that we can reduce the rate of global warming by consuming less meat and dairy products4. Eliminating  meat from the diet reduces greenhouse gas emissions by approximately 50% because there are fewer methane-producing animals required to produce food 5. In contrast, fruit and vegetable production draws down carbon dioxide through photosynthesis. So even just reducing the number of times you eat meat per week will make a difference. On top of this, to provide the same amount of nutritious food, meat production uses up more land as pasture than growing fruit and vegetables. So when gardeners grow fruit and vegetables at home or in a community garden or replace beef, lamb and pork consumption with eggs from their own chooks, they are making a contribution to slowing climate change,

meat from the diet reduces greenhouse gas emissions by approximately 50% because there are fewer methane-producing animals required to produce food 5. In contrast, fruit and vegetable production draws down carbon dioxide through photosynthesis. So even just reducing the number of times you eat meat per week will make a difference. On top of this, to provide the same amount of nutritious food, meat production uses up more land as pasture than growing fruit and vegetables. So when gardeners grow fruit and vegetables at home or in a community garden or replace beef, lamb and pork consumption with eggs from their own chooks, they are making a contribution to slowing climate change,

If you are taking those actions already, you also know about the added health benefits. More plant-rich diets address many of the increasingly frequent health issues including heart and circulatory problems 6, some forms of cancer 7 and even rheumatoid arthritis8 by reducing dependence on red meat.

Reduce Shopping Miles

Grow Your Own

If you grow your own fruit and vegetables, even just a few on a balcony or courtyard, you are reducing food miles (a measure of carbon-based fuel used to get food to you) as well as making the contributions to reducing carbon emissions described above.

But there is a lot more we can do regarding our levels of consumption.

Buy Locally

We are hardly ever totally self-sufficient for food and still purchase items which may have travelled many miles to reach us, using fossil fuels in the process. So let’s try reducing food miles by buying what we can’t grow ourselves from local growers when we cannot produce it ourselves – think Farmer’s Markets, Harvest Swaps and foraging for food.

We can seek out other items for the garden e.g. furniture, stakes or pots, which are produced in Australia – or even better in our own state – rather than those that are imported. This may mean a higher financial cost, but that may encourage us to either make our own or reduce our overall material consumption.

Reduce, Reuse, Recycle

We can become thrifty gardeners!

Being clever about minimizing our purchases, reusing items and recycling what we can’t reuse in their current form means less waste, less resource use (including less coal-fired electricity) and less waste going to landfill which would lead to methane production.

For example, we can minimize use of plastic pots for seedlings by making containers using the centres of toilet rolls as the sides and some newspaper in the bottom. In fact, newspaper can be used to make complete seedling pots. Both alternative types of “pot” are also better for seedlings since the whole “pot” plus seedling can be popped directly into a garden bed without disturbing the roots – the cardboard or paper will gradually decay.

Some clever ideas for reusing and recycling in the garden have been used in the garden of one of SGA’s subscribers. Recycled materials can be used for garden edging and garden art.

So we can be creative, enjoy our gardens, build our local communities and be healthier, more comfortable and save money at the same time as helping alleviate the rate of global warming.

References

-

https://www.csiro.au/en/Showcase/state-of-the-climate

-

www.bom.gov.au/state-of-the-climate/

-

Baldocchi D, Penuelas J. (2018). The physics and ecology of mining carbon dioxide from the atmosphere by ecosystems. Climate Change Biology https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14559

-

Hedenus F, Wirsenius S, Johansson DJA (2014) The importance of reduced meat and dairy consumption for meeting stringent climate change targets. Climatic Change. 124 (1–2): 79–91.

-

Hoolohan C Berners-Lee CM, McKinstry-West J, Hewitt CN. (2013) Mitigating the greenhouse gas emissions embodied in food through realistic consumer choices. Energy Policy 63: 1065-1074.

-

McEvoy CT, Temple N, Woodside JV (2012) Vegetarian diets, low-meat diets and health: a review. Public Health Nutrition 15 (12): 2287-2294.

-

Prashanth Rawla, Tagore Sunkara, Adam Barsouk (2019) Epidemiology of colorectal cancer: incidence, mortality, survival, and risk factors.

-

Philippou E and Nikiphorou E. (2018) Are we really what we eat? Nutrition and its role in the onset of rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmunity Reviews 17(11): 1074-1077

Newbie Sustainable Gardener in COVID Times

Extra time at home spurred an SGA subscriber to become a newbie sustainable gardener by starting her own veggie garden. Amy Esdaile tells us of her experience.

" When I wake up in the mornings, I first check out my window. Has the sun risen? Does it appear windy? Signs of rain from last night? I check the weather for the day ahead of me and I do so because I have become very attached to my growing garden.

My first gardening endeavour was when I noticed sprigs of thyme had been left in the fridge for long enough and I had yet to use them in any dishes. I decided to stick some in the ground. Upon searching for information for growing Thyme off the SGA website, I knew it was relatively low-maintenance and I figured, I’d see if it would grow. My thyme is flourishing.

My first gardening endeavour was when I noticed sprigs of thyme had been left in the fridge for long enough and I had yet to use them in any dishes. I decided to stick some in the ground. Upon searching for information for growing Thyme off the SGA website, I knew it was relatively low-maintenance and I figured, I’d see if it would grow. My thyme is flourishing.

I loved heading out into the backyard to see how the thyme was doing and I endeavoured to try and create a good bed of soil following many tips I’d collected from a book I’d purchased called The Edible Garden by Paul West (from River Cottage Australia).

I’ve since grown sprouts in a jar, popped some carrots in the ground (that had started sprouting roots in the fridge) and  have some strawberry punnets full of potting mix developing seedlings on windowsills.

have some strawberry punnets full of potting mix developing seedlings on windowsills.

Watching my plants puts a grin on my face, has helped me conquer fears of creepy crawlies  and has given me the rewarding purpose of watching something I’ve nurtured and fed, rise up from the soil and grow, continuing to discover new potentials every day.

and has given me the rewarding purpose of watching something I’ve nurtured and fed, rise up from the soil and grow, continuing to discover new potentials every day.

Gardening is a process, and during COVID-19, I am thankful for it. I would have found getting out of bed significantly harder to achieve without the help of my watering can and gardening gloves."

Thank you, Amy, for sharing how some simple gardening task can lift our spirits as well as provide something edible.

The Samphires

Looking for an easy to grow, attractive, edible, nutritious perennial succulent? Then the samphires (not the British band . . . ) are the answer. Their name comes from their ability to grow in salty environments in either dry, rocky areas or coastal marshes. It’s derived from the French “Saint Pierre” who was the patron saint of fishermen. Different species have adapted to these environments in different parts of the world. The best known are Rock Samphire, Crithmum maritinum and marsh samphire Salicornia in Britain and Tecticornia in Australia. Since they are in different plant families there is some confusion in descriptions of how to use them.

Rock Samphire

Originally a wild plant on the coasts of Europe as far as the Black Sea and north Africa, Rock Samphire (also called Sea Fennel) was hailed a vegetable that would prevent scurvy and was widely used by sailors in the 17th century. In addition to vitamin C it is also high in vitamins A, B2 and B15 and in minerals. Traditionally, it was pickled and sold from large barrels. It was also popular in the Victorian era. It grew in places many other plants avoided i.e. rocky cliffs and crevices along the coast where it was exposed to salt. Its persistent popularity, coupled with extensive over-development of coastal regions led to it being given protected status in 1971 in Great Britain. Now it is available from specialist herb and vegetable nurseries, including here in Australia.