Many professionals in the gardening and landscaping industry are exploring ways of creating more sustainable landscapes.

Water Sensitive Urban Design (WSUD) is the hot topic of discussion amongst landscape professionals and even developers, who are now being instructed by legislation to ensure WSUD is incorporated into their developments.

WSUD?

So, what is it?

It’s only one of the most significant changes in urban design in recent years. It is the practice of keeping stormwater on site, at least for as long as possible, rather than sending it immediately into the stormwater system. An important aspect of this is porous paving, or types and styles of paving and surfaces that encourage rainwater to infiltrate the soil, rather than run off.

Hectares and hectares of hard surfaces across urban areas have meant cities are susceptible to flash floods, and huge volumes of pollutants are flushed into waterways. By slowing down the rate at which stormwater enters the system, a lot of the pollutants are captured, and the incidence of flooding is reduced. These hard surfaces also contribute significantly to the heatbank of a city.

This contemporary Melbourne landscape was designed by David Bennett of Gardens by Design and constructed by Winstanley Landscapes. It not only features WSUD initiatives, but lots of other sustainable features as well.

‘The existing top soil was scraped to one side and stored on site,’ explains Dave Bennett. ‘When landscape works were completed, the top soil was amended and laid back over, to provide a reasonable planting environment. This also reduces cart away to tips and landfill sites.’

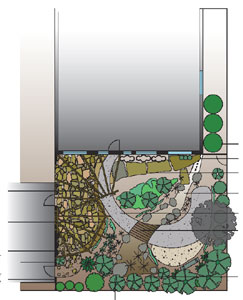

This landscape has only recently been completed, so most of the plants, especially larger shrubs and trees, have quite a bit of growing to do. When the landscape is mature, as can be seen in the coloured landscape plan here, the vegetation will be quite dense. Fences and neighbours will be screened, the garden will be a haven for birdlife, and an oasis for its owners.

The before photos show what a transformation took place! The concrete was pulled up, sent to a nearby recycler where it was turned into crushed rock. The same material was used as a compactable sub-base under wall footings and paths.

A dry creek bed traverses the space and acts as more than just a feature. It helps capture and retain stormwater onsite. The river pebbles are from a local, controlled source, rather than from indiscriminate river mining operations that take place in Asia.

‘We used porous paving wherever we could,’ says Dave, ‘to reduce runoff from the site. And even where we had to use non porous surfaces, they are sloped to run into the creek bed.’

The plants are drought tolerant Australian species that provide a variety of foliage textures and colours and a variety of flowers, including grevilleas, a smaller growing Eucalyptus, a mass planting of an elegant weeping shrub Acacia cognata ‘Limelight’, and even one of Australia’s few deciduous trees, Melia azederach (White Cedar).

The area to the left in the photo shown here will be densely planted over time. In the foreground, those little green clumps will become metre-high, elegant weeping shrubs and behind, the small growing Eucalyptus preissiana (Bell-fruit Mallee) will grow to about 4 metres tall.

In the foreground these kangaroo paws will soon grow into a large clump. In the background a timber bridge takes a path over the dry creek bed that weaves through the landscape. Over time, the fence will be screened by plants.

The existing sheds were retained but were cleverly screened using plantation-grown, radial sawn timber (see image at the top of the page). The technique of radial sawing ensures more useable timber is taken from a log. In the foreground, the two dominant, strappy leafed plants are Doryanthes excelsa (Gymea Lily), which grow into very large clumps with leaves reaching 2 metres long. The stunning flower stems can grow up to 6m high.

Castlemaine slate was chosen for the paving and the stonework, not just because it’s a beautiful material, but also because it is a local material, and a concept similar to ‘food miles’ was considered. This refers to the distance a resource must travel – the closer resources are to the site, the less impact on global warming. The slate offcuts were used as inorganic mulch.

The design also includes two rainwater tanks and a greywater treatment system, but these inclusions are on hold for a year. The owners are not likely to need an irrigation system so they are going to review their water use over a year.

Photographs courtesy of Yarrabee Castlemaine and Gardens by Design.

A full version of this article appears in Renew (The Alternative Technology Association’s magazine), September 2007.

Related Articles:

Citizen Science: A Pathway to Gardening Success and Biodiversity Conservation

In recent years, the realm of science has experienced a remarkable transformation, one that invites people from all walks of life to participate…

A Sustainable Gardener’s Guide to Thrifty Gardening

Creating an eco-friendly and cost-effective garden involves more than just nurturing plants; it's about adopting a sustainable approach that…