When I started experimenting with wicking beds a few years ago, I was concerned about the isolation of the wicking bed’s soil. The bed’s water tank was an effective barrier to the biodiversity in the rest of the garden, so I decided to fit a build-in worm farm and populate it with composting worms to try to maintain a viable separate ecosystem.

It soon became apparent, that soil fertility required more than the worm farm could deliver, and composting worms were not the best species to distribute their vermicasts throughout the bed.

I started to populate the bed with earthworms from my compost heap and garden beds. I top dressed the soil with compost and rockdust under a thick mulch of straw. I did this every time I harvested a crop in preparation for the next one, leaving it to “mature” for several weeks before planting. I found lots of earthworms in the compost residue when I planted my new crop, and crop health and growth rate improved noticeably.

Colin Austin in his blog Waterright began to talk about the symbiotic relationship formed between mycorrhizal fungi and the plants through their roots, and how he sets up bio-packs to establish a mycorrhizal network of hyphae (an extremely effective micro root system) which new plants can hook into and share. His interest prompted me to research soil biology on the net to see if I could understand it better.

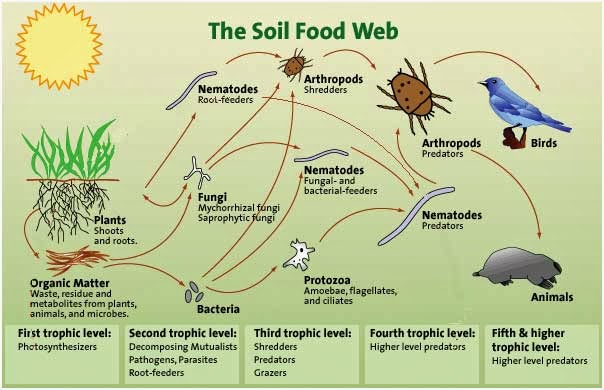

I came across the Soil Foodweb Inc., and Dr Elaine Ingham who provided some very interesting insights through her series of YouTube interviews, SOIL not DIRT. She explains the soil food web as a system involving an extraordinary diversity of organisms living in their billions in natural soil including earthworms, bacteria, fungi, nematodes, arthropods and protozoa.

The soil food web includes the plants and animals above ground which are so dependent on the activities of the organisms in the soil. They help feed the microbes with their waste including dead and decaying organic matter.

In natural soils, earthworms (and other small animals and insects) harvest this organic material from the surface and drag it underground. They consume it and, in the process, shred and grind it so that when evacuated from their bodies it is in a form which is perfect for the microbes to feed upon. Bacteria, fungi and nematodes break down this material, rich in essential minerals, and liberate more minerals from sand and clay particles in the soil. They absorb these essential minerals into their bodies, and their predators convert the minerals into a form easily assimilated by the plant’s roots. Note that the sand and clay particles have been formed over millions of years from geological action on the parent bedrock and that is the primary source of all the minerals used by the plants to make our food, in natural soil.

This intense activity by the soil organisms, not only provides readily available food for the plants, they create a structure in the soil which enables free movement of air and water, and easy passage for roots as they grow. Water drains easily through this structure so that the soil does not stay wet for too long, but also retains some of the moisture, so the soil does not dry out too quickly.

It’s a well known saying amongst organic gardeners that you should feed the soil not the plants. I don’t know whether old time gardeners realised this meant feeding the microbes. Anyway, I now realise why it is so important to maintain the soil food web, and that using pesticides, herbicides and inorganic chemical fertilisers is such a bad idea.

Like Colin Austin, I am keen to convey the message to as many people as will listen, that industrial agriculture with its dependence on synthetic inorganic fertilisers is producing food so deficient in vital micronutrients, that we are becoming dependent on supplements to maintain bodily health. Why would you not eat organic food, and preferably, grow your own in your own garden.

If you are interested in my quest to develop a gardening system which uses very little water, which sequesters carbon and is as sustainable as I can make it, take a look at my non-commercial blog from time to time.

Article copyright to John Ashworth.

Photo: The Soil Foodweb Institute

Related Articles:

The Importance of building soil health for a biodeverse, productive garden

Creating a thriving garden that not only sustains itself but also contributes to the broader ecosystem requires more than just sunlight and water.…

Soil as a Carbon Store

Rather than regarding soil as just a medium for growing plants, we should also be viewing soil as a carbon store. This means that it is an important…