We see them on the roadsides: vigorous, long-flowering, hardy and a splash of colour against the grey-green foliage of the native species. They are weeds and it is their hardiness that makes them such a threat to endemic species. Environmental weeds invade native ecosystems and adversely affect indigenous flora and fauna. There are now more foreign plants in Australia than native ones: about 27,500 introduced plant species have made their way into the country, compared with 24,000 native species. Around ten per cent of the ‘invaders’ have become ‘naturalised’.

Environmental weeds were introduced as ornamental species for domestic gardens. They are survivors as they have relatively few natural diseases, insects or pests to control their populations, and can out-compete native species. Disturbed sites are havens for weed species as many thrive in poor soils and then smother existing native species. They can have significant health, economic, environmental and social impacts (Ragweed, Gorse, Rubber Vine and Salvinia, respectively). They also have larger environmental impacts such as degradation of water quality and increased risk of fire, loss of ecotourism opportunities, the costs associated with control, impacts on recreational activities and the landscape, and the reduction of biodiversity.

Environmental weeds were introduced as ornamental species for domestic gardens. They are survivors as they have relatively few natural diseases, insects or pests to control their populations, and can out-compete native species. Disturbed sites are havens for weed species as many thrive in poor soils and then smother existing native species. They can have significant health, economic, environmental and social impacts (Ragweed, Gorse, Rubber Vine and Salvinia, respectively). They also have larger environmental impacts such as degradation of water quality and increased risk of fire, loss of ecotourism opportunities, the costs associated with control, impacts on recreational activities and the landscape, and the reduction of biodiversity.

Indigenous weeds

Weed scientist, Dr. Richard Groves from CSIRO and the Weeds Cooperative Research Centre (Weeds CRC) describes the difficulty in determining the difference between ‘native’ and ‘indigenous’ or ‘endemic’ plants. “The Oxford Dictionary defines ‘native’ as the place or country in which you were born, and ‘indigenous’ as native to the soil region etc. A plant may be indigenous to a wet gully and native to SE Australia, or indigenous to the Dandenong Ranges and native to Australia”, notes Dr. Groves1. The point at which an invasive indigenous plant starts becoming a weed is often difficult to define, and often too late.

Fluctuations in indigenous populations (generally due to human interference) make the issue even more complex. The lack of bushfires in Wilsons Promontory National Park, for example, has led to Leptospermum laevigatum (Coastal Tea Tree) rapidly overtaking endemic plant communities. Pittosporum undulatum (Native Daphne) is another example of a native species literally destroying the ecosystem of bushland remnants west of Westernport Bay in Victoria. It is planted widely as an ornamental tree, and animals and birds readily disperse its fruits; it is also highly adaptable and more moderate and changing fire regimes have allowed its growth to continue – previous and hotter burns would have destroyed it. This adaptability means it successfully outcompetes other species, through shading, depletion of soil moisture and nutrients, and loss of habitat for animals. A list of top twenty weedy Australian native plants in Victoria compiled by Geoff Carr of Ecology Australia includes three Hakea species, eight wattles and three Melaleuca species.

About 200 species in Victoria have ‘naturalised’ outside their native range. A much cited example is the Cootamundra Wattle Acacia baileyana, which competes with native shrubs, small trees and ground flora, and impedes their regeneration. Not only is it a serious threat in an extraordinarily broad range of environments, it is also reportedly hybridizing with at least six other Australian wattles. This threatens the integrity of native wattle populations through genetic pollution, particularly when two of these species (Acacia decurrens and Acacia dealbata) are also environmental weeds outside their native ranges.

Government legislation on weeds

The Australian Government maintains national weeds lists, the nature of the weeds, and the resulting national actions required, determine on which lists a species may appear (see www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/invasive/weeds/index.html). These lists and the recommended actions against specific weeds are vital guides for gardeners, nursery owners and propagators, plant importers and landscape industry, as is the social awareness that comes with purchasing, specifying or propagating a plant that may exact heavy costs in the future.

For the home gardener, ‘Grow Me Instead’ (GMI) is an initiative of the Nursery and Garden Industry Australia. Funding from the Australian Government has enabled the publication of Grow Me Instead ™ guides for each state and territory. These guides identify offenders and list several non-invasive alternatives for each, and are one valuable element of this integrated and multidisciplinary approach. Plant nurseries generally take care when supplying stock that might be on Declared Weed lists – take care however when purchasing at markets or online as many declared weeds are still propagated.

Plants to avoid

In Queensland, plants that are still available (yet listed as Class 1, 2 and 3 Pest Plants) include:

Gleditsia spp. (Honey Locust) (Class 1 – ‘potential to become very serious pest’)

Thunbergia grandiflora (Bengal Clock Vine) (Class 2 – ‘already spread over substantial areas’)

Hedychium gardnerianum (Kahili Ginger) and Hedychium coronarium (White Ginger) (Class 3 – ‘commonly established’)

In NSW, seek substitutes for pest species such as:

Acacia baileyana,

Acacia podalyriifolia

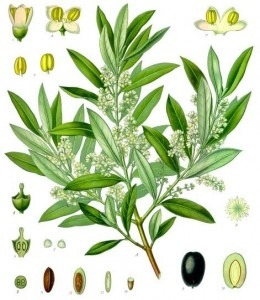

Olea europaea ssp. Europaea

In Victoria avoid:

Acacia baileyana

Acacia saligna (Golden Wreath Wattle)

Melaleuca armillaris spp. armillaris (Bracelet Honey Myrtle).

Article and photographs by Dr. Catriona McLeod who is a writer, environmental & cultural consultant, horticulturalist and designer based in Tasmania. With a PhD in green design, she has taught design theory and principles, landscape architecture, ecology, horticulture and sustainable practices at the University of Tasmania. She is a passionate advocate of wild places and the preservation of threatened environments and species and is, of course, an avid and ever-learning gardener. www.catrionamcleod.com

References

1.Weed Society of Victoria. Can Australian Native Plants be Weeds? How big is the problem? http://www.wsvic.org.au/node/27

Related Articles:

Wildflower gardens – What’s the buzz about?

In the quest for sustainable and environmentally conscious practices, gardening enthusiasts and nature lovers alike are turning to a time-tested…

Weed Control

Several different approaches are needed for weed control since eradication is difficult and can be expensive. Preventing weeds from establishing and…